Volume Thirteen – 1901 – 1922

The Edwardians and the Great War

KING EDWARD: A LIFE OF PLEASURE

THE BOER WAR

A THEATRICAL LEGEND

TOURING THEATRE COMPANIES

THE STRENGTH OF CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN

KEIR HARDIE

MOTORING

KENNETH GRAHAME

EDWARD ELGAR

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

KING EDWARD: A LIFE OF PLEASURE

As the Prince of Wales, and later as King,

His mistresses (a veritable string)

Were received as part of the royal scene,

Which purists found a trifle obscene.

There was Hortense Schneider (one of the first);

Daisy ‘Babbling’ Brooke (surely the worst,

A right royal gossip); Lillie Langtry

(Graceful, voluptuous and willowy,

An aspiring actress); then, what a wheeze,

The Hon. Mrs. Keppel, his final ‘squeeze’.

The Queen was tolerant of Mrs. K,

Who had planned to call on the very day

The King died. She was due at five o’clock,

But the poor Queen suffered a cruel shock

When she saw her husband. As was her way,

She summoned Mrs. Keppel right away.

However sad she was, and woebegone,

Queen Alexandra had her head screwed on.

As the Prince of Wales, a life of pleasure

Was his happy lot. He took his leisure

(Women apart) at country house parties,

Shooting, yachting with nautical hearties,

And indulging his awesome appetite

At dinners and banquets, night after night.

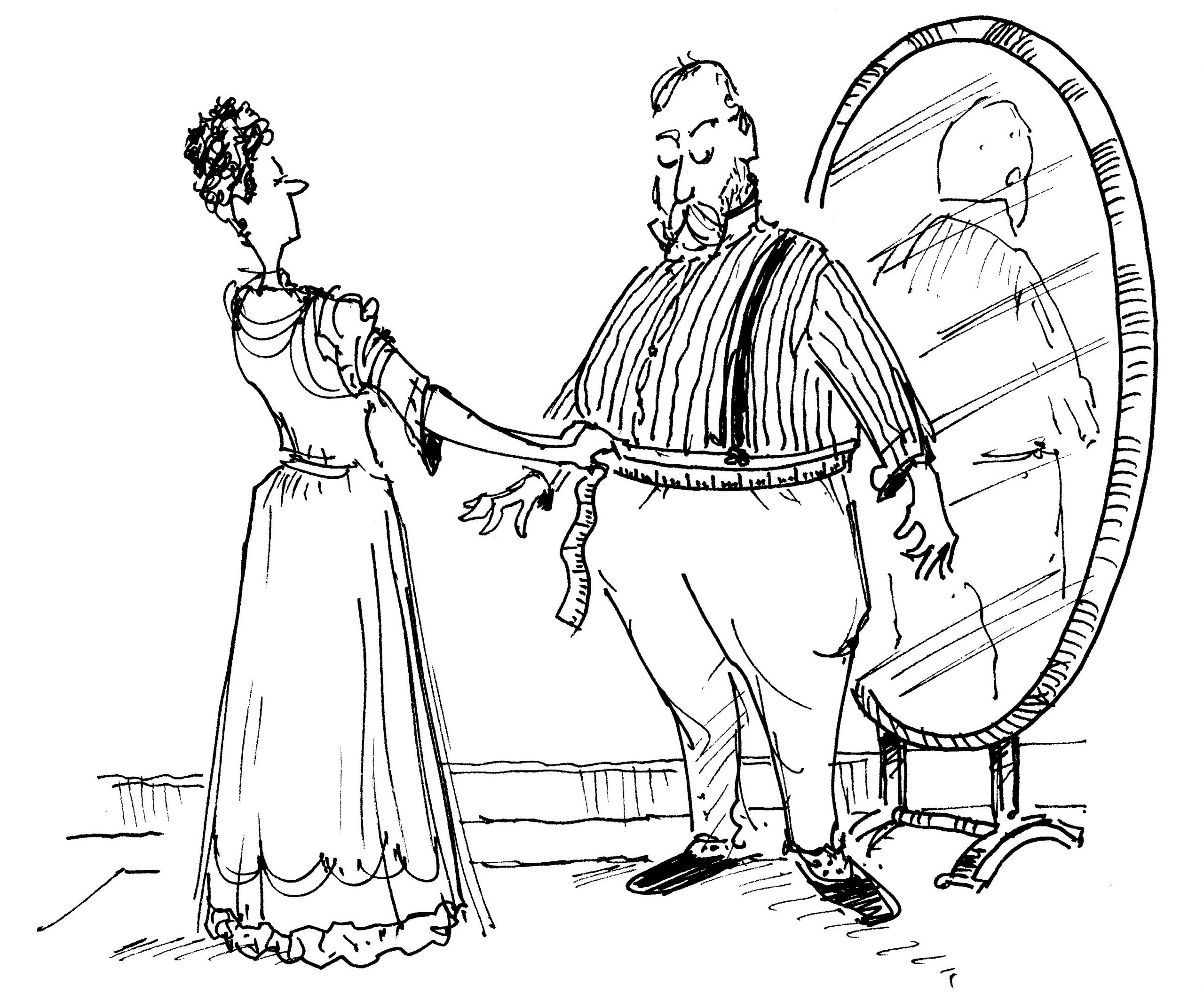

His elegant wife got a fearful fright,

Happening to take her tape measure out

To measure his waist. She knew he was stout,

But forty-eight inches..! Without a doubt,

Old Queen Victoria was most put out:

Her son was all that her Albert was not.

With Bertie the country would go to pot.

Lord Salisbury was in broad agreement,

His first Prime Minister. No concealment

Did he make of his personal distaste

For Bertie’s habits. The Prince never graced

Hatfield House as an honoured private guest.

Lady S. in person, Heaven be blessed,

Supported her husband’s royal veto.

There were times one simply had to say no.

THE BOER WAR

The Boer War was as good as won,

Or so it was thought, by 1901.

The truculent Boers were sorely vexed.

The Transvaal had been formally annexed

By the Brits, also the Orange Free State.

Death to the Boers! Defeat was their fate!

Lord ‘Bobs’ Roberts, the Commander-in-Chief,

Returned home in triumph. It’s my belief

He was lucky, for the dispossessed Boer

Bit back with a vengeance. The costly war

Was not yet over. Roberts’ successor –

Apple of the late Queen’s eye, God bless her –

Was General Kitchener, Chief of Staff,

Promoted to Commander. Tough? Not half!

In the face of the guerrilla warfare

Waged by the Boers, you should be aware

That Horatio Kitchener played hard.

Government policy was ‘no holds barred’.

Prime Minister Salisbury maintained throughout,

“You will never conquer” (he had no doubt)

“These people until you have starved them out”.

The facts were stark. The guerrillas attacked

Railway lines; military camps were sacked,

Telegraphs destroyed. So the British burned

Their farms and homesteads. Lessons would be learned

If, but only if, the Boers concerned

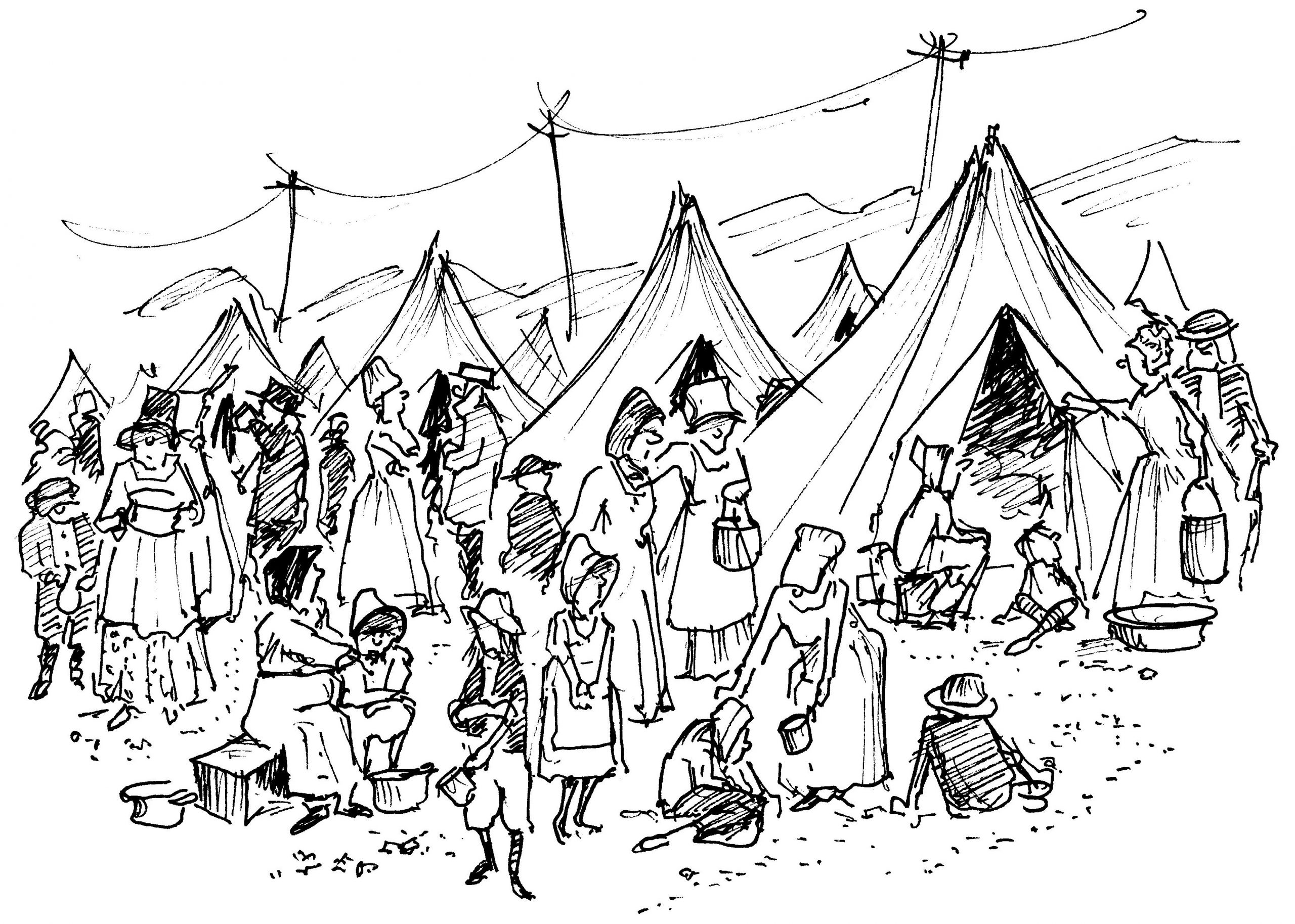

Were pursued across the veld. The distress,

Imagine, of their families! Homeless,

The women and children, virtual tramps,

Were ‘concentrated’ into ‘rescue’ camps.

They were never captives. The irony

Is that their presence was voluntary.

But the refugees had nowhere to go,

And even the Boers, I’ll have you know,

Destroyed the homes of those who surrendered.

The hatred and bitterness engendered

By these foul places was beyond belief.

Tens of thousands of poor souls came to grief

In the concentration camps. Typhoid,

Hunger, dysentery (hard to avoid),

Claimed many lives. Some 20,000 died,

A terrible toll that can’t be denied.

Kitchener and his ilk must share the blame.

Campbell-Bannerman (remember that name),

Liberal leader, asked “when is a war

“Not a war?” People were wont to ignore

The truth. “When it is carried on,” he said,

“By methods of barbarism.” Instead,

Why not sue for peace? Whatever one’s views,

The Boers resembled “the widow’s cruse” –

So wrote Salisbury: “the more you kill,

“Or take, the more there are”. For good or ill,

The stubborn Boers refused to accept

Their pitiful plight. What did they expect?

The Brits to cave in? The time had to come

When the bold Boers would have to succumb.

To the British, too, it is my belief

That peace would come as a welcome relief.

6,000 soldiers died, if you please,

In the field, 10,000 more from disease,

With 23,000 poor men wounded –

And the cost? Two hundred million quid!

These were just the British figures. Who knows

How many Boers? We’re led to suppose

It was their sheer pig-headed resistance

To British rule, their blinkered insistence

On independence, that prolonged the war.

I am not prepared though to blame the Boer.

Back to top / Buy the book

A THEATRICAL LEGEND

Sir Henry Irving took his final bow

In 1905. Now don’t ask me how,

But Irving triumphed theatrically,

Despite his awkward physicality,

His bad stammer, puny legs and flat voice.

The theatre seemed a curious choice

For such as him, but against all the odds

He made the grade. They fainted in the gods

During The Bells. The critics were struck dumb.

Sir Henry’s long reign at the Lyceum,

As actor-manager (twenty-three years),

Crowned this most surprising of careers.

He was knighted in 1895

By Queen Victoria. No man alive

Did more in his time to raise the profile

Of actors. Glamour was never his style.

In later life he went back to touring:

Becket, a dud by Tennyson, boring

And turgid, and The Bells, popular still.

Irving was ailing – nay, mortally ill;

A blaze had destroyed his scenery store;

He’d quit the Lyceum some years before.

The poor old soul couldn’t take any more.

Yet Irving staggered on, ever the pro.

He died in harness (what a way to go),

Following a barnstorming performance

As Becket. By chance, in the audience,

Was Athene Seyler*, then aged sixteen,

Who fainted clean away at his death scene.

He breathed his last in a Bradford hotel.

He was sixty-seven. Irving did well.

An elderly actor, it’s not much fun

Touring the provinces. His day was done.

Back to top / Buy the book

TOURING THEATRE COMPANIES

What of the provinces? Theatres thrived

In Edwardian times. Few have survived,

But (without counting buildings in London)

The total number, in 1901,

Was some two hundred and sixty or more –

Rich pickings for actors willing to tour.

Francis Robert Benson, aged twenty-four,

A novice in a touring company

Run on a shoestring by Walter Bentley,

Assumed the reins in 1883,

When Bentley ran off. Decidedly rash!

Raw, inexperienced and strapped for cash,

His life as a manager had begun.

Having renamed it the ‘F. R. Benson’,

Frank devoted himself, for forty years,

To touring. There were setbacks, there were tears,

But during this most bizarre of careers,

He produced every play of Shakespeare’s

At Stratford, barring only, it appears,

The rarely performed Titus Andronicus

And Troilus and Cressida. Why the fuss?

Well, Benson’s lifelong association

With Stratford enhanced his reputation,

But, more importantly, it became clear

That the public had a thirst for Shakespeare.

His productions were spare, scholarly,

Simple and plain – quite unlike those of Tree.

Benson took out more than one company

To play different parts of the country –

North, south and midlands simultaneously.

The old image of the ‘actor laddie’

Fitted his character down to a T.

Yet it remains a striking irony

That if it was the play you wished to see,

Without an excess of flim-flammery,

You’d head for the provinces. Poverty,

It appears, was no bar to quality.

During the Shakespeare tercentenary,

Benson was knighted. In the royal box

At Drury Lane, bless his cotton socks,

Sir Frank he became. Hardly a disgrace,

For this proved to be the very first case

Of an actor receiving his knighthood

In a theatre. Perhaps they all should.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE STRENGTH OF CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN

CB, as a House of Commons speaker,

Was dull and tedious, no one weaker.

Well, that was the broadly accepted view,

But his colleagues now witnessed something new –

A sharp, dynamic Campbell-Bannerman.

CB was suddenly the coming man.

Arthur Balfour had lost his Commons seat.

He was re-elected, back on his feet,

As Member for the City of London –

A hasty by-election: deal done.

Leading for the Tories, in a debate

On free trade, Arthur sought to obfuscate,

To blind the Commons with “airy graces”

(CB’s phrase), kicking over the traces

With a languid speech full of irony,

Paradox and anguished imagery –

More in the manner of Disraeli

Than a serious politician

Of the modern age. No contrition,

No humility, did Balfour display.

CB lost his temper. High time, I say.

“Enough of this tomfoolery,” he cried.

The force of his put-down can’t be denied.

This “light and frivolous way of dealing

“With great questions” was unappealing.

These tactics “might have answered very well

“In the last Parliament” (you can tell

How cross he was) – they were “altogether

“Out of place in this!” Light as a feather,

He hit his mark. A change in the weather?

I’ll say! Far from having barely survived,

A new Campbell-Bannerman had arrived.

Even the old King began to mellow.

CB, if you please, was “a good fellow”,

Edward having run into him, by chance,

At Marienbad. His ‘pro-Boer’ stance

Was largely forgotten, apparently,

As the King (who’d expected him to be,

By his own account, “prosy and heavy”)

Found him to be “very good company”.

They rarely talked politics, however.

One reporter, trying to be clever,

Who saw the two with their heads together,

Printed the headline, “Is it peace or war?”

When asked, CB had a surprise in store.

The King had only been asking his view

“Whether halibut” (I swear this is true)

Was “better baked or boiled”. A pleasant chat

Between two old gents, as simple as that.

Back to top / Buy the book

KEIR HARDIE

The first leader of the Labour Party

Was the indomitable Keir Hardie.

In the 1906 Parliament,

The fledgling party, by common consent,

Achieved a breakthrough: twenty-nine MPs.

This was up from a mere two, if you please,

In 1900, when Keir Hardie

(Merthyr Tydfil) and Richard Bell (Derby)

Were both elected. Hardie’s first success

Had been in 1892, no less,

As the Independent Labour MP

For West Ham South. Returned for Battersea

Was J. W. Burns. They lost their seats

In the worst of electoral defeats

In 1895. Labour: zero!

But Hardie was the party’s first hero.

A working miner, he was widely read.

He taught himself Pitman’s shorthand, it’s said,

Down the mine. Before he was twenty-five

He left the pit, and managed to survive

As a shopkeeper, then a journalist,

And later as a trade unionist.

He became the full-time secretary

Of the Ayrshire miners. The young Hardie

Was in his element. Unionism

Led him to embrace socialism.

Keir deplored the bloody suppression

Of striking miners and the aggression,

Which he witnessed, of the police. Appalled,

He nailed his colours to the mast and called,

Openly, for the peaceful overthrow

Of capitalism. Who was to know

That Keir Hardie, by 1906,

Would have changed the face of British politics?

Hardie’s Independent Labour Party

(ILP) and the so-called LRC

(Labour Representation Committee)

Came together as the Labour Party

In 1906. This new unity

Fostered a greater strength in the movement

And led to a progressive improvement

In campaigning power and influence.

The forging of a ‘labour alliance’

Between the party and the TUC

Was an overwhelming necessity,

But this occurred only gradually.

However, after the Taff Vale judgement,

It was clear that only Parliament

Could remedy the patent injustice.

It was the growing awareness of this

That brought the bigger unions on side.

A political base? Time to decide!

Keir Hardie did not go unheeded:

A strong voice in the Commons was needed.

Back to top / Buy the book

MOTORING

The motor car was the toy of the rich.

Watch out, or you could end up in the ditch

As a Daimler or Mercedes sped by.

No more red flags, that was the reason why.

For before to the turn of the century,

A fellow with a red flag, for safety,

Had to walk in front of a motor car.

Needless to say, it could not travel far

(Let alone fast). The British, to be blunt,

Were slow off the mark. Leading from the front

Were Germans: Gottfried Daimler and Karl Benz.

I have no desire to give offence,

But engineers like Morris and Austin,

For all their skills, barely got a look-in

During those first, experimental years.

And yet these two dynamic pioneers

Grew in strength to become the true giants

Of Britain’s car industry. Their clients

Belonged to the lower and middle band

Of the market. Their cars were hardly grand,

But they were cheap! The company of choice,

Of course, for the upper class, was Rolls-Royce.

Royce was an electrical engineer.

He was cool and reserved, it would appear,

With the Hon. Charles Rolls on first acquaintance.

Both men, to be frank, were high maintenance.

Rolls was a high-class salesman. Truth to tell,

His was the most exclusive clientele,

And when a Rolls-Royce won the Manx Grand Prix,

In 1906, I’ll tell you for free

That their name was made. “Not one of the Best – ”

Was their early slogan: folk were impressed –

But “The Best in the World.” And so it proved.

Rolls-Royce led the way, and the world approved.

Back to top / Buy the book

KENNETH GRAHAME

Now in my view the novel of the age,

A feast of wonders on every page,

Is The Wind in the Willows. Ever billed

As a children’s story, you will be thrilled,

I promise you, when you pick up this book

As an adult. Do take a second look.

For this charming tale of the river bank,

A gem, we have Kenneth Grahame to thank.

The entirety of his working life

He spent at the Bank of England. His wife

Always claimed that The Wind in the Willows

Was for their son – propped up on his pillows,

In bed, an invalid child. True or not,

This “messing about in boats” (what a plot!),

The tale of Ratty, Mole, Badger and Toad –

The latter ‘a-toot’ on the open road –

Was a hit when Methuen published it.

All other publishers had rubbished it.

Methuen decided to take a chance,

But refused point blank to pay an advance –

Too risky. Three little furry creatures

And a toad! Well! The novel’s finest features

Are its dialogue (witty, down to earth

And human) and, of still more sterling worth,

Its descriptions: never overdone –

Nay, pitch perfect. The rising of the sun,

The peace of the river, the dawn chorus,

The reeds and poplars: the prose is gorgeous,

But never pretentious. It was this

That the critics loved, but (easy to miss),

In Grahame’s words, “they did not even notice

“The source of all the agony, all the joy”

That went into “those playful pages”. Oh, boy!

That says it all and perhaps explains why

The Wind in the Willows will never die.

Perfection in a book is a rarity.

Kenneth Grahame achieved it, believe you me.

Back to top / Buy the book

EDWARD ELGAR

Parry set the bar high. Edward Elgar,

In his day, was an even brighter star.

Sir Hubert’s junior by just nine years,

Elgar was more than a match for his peers.

He was a late starter, pushing forty

When, for the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee,

In 1897, he composed

His Imperial March. No one supposed,

At the time, that Elgar would reach the heights.

But fame was the spur. Edward set his sights

On greatness. He had led a humble life,

Tied to his father’s music shop. His wife

Encouraged him in his ambition.

He was self-taught in composition,

Studying Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart…

Harmony, counterpoint… Where do I start?

He played organ, bassoon and violin,

But knew, in his soul, he cared not a pin

For performance. So he began to write.

He would compose a new piece, overnight,

For his and his brother Frank’s wind quintet:

Oboe, bassoon, two flutes and clarinet –

Every week, a completely new set.

Edward struggled, and would have come to grief

Had it not been for honest self-belief

And the support of his dear wife, Alice.

By all means give his early works a miss,

But in 1899 he struck gold.

Who among his critics could have foretold

That his Enigma Variations,

One of Elgar’s rarest creations,

Would become one of the sensations

Of the age? Not his wife’s relations,

That’s for sure. They opposed the marriage

And did their level best to disparage

Young Edward’s talents. His true genius

Shone through in The Dream of Gerontius,

Which was first performed the following year.

Early notices were lukewarm, I fear.

The work was under-rehearsed. Nonetheless,

Gerontius became a huge success,

The finest oratorio, no less,

In English, since George Handel’s Messiah.

Edward Elgar, it seems, was on fire.

His first Pomp and Circumstance March (in D)

Had the Queen’s Hall, London, in ecstasy.

It’s true! The conductor, Sir Henry Wood,

Was keen to move on, if only he could,

But the audience insisted on more.

So Sir Henry gave them a full encore.

This, apparently, was still not enough!

Pomp and Circumstance was very strong stuff.

Elgar was well and truly on the road

To fortune. His Coronation Ode

(1902), at the suggestion

Of the King, used the trio section

From Pomp and Circumstance. A. C. Benson

Wrote the words. Thus Land of Hope and Glory

Was conceived, and the rest is history.

This was published as a separate song

And is sung, today, to jolly along

The Last Night of the Proms. Encore! Encore!

Elgar was knighted in 1904.

There were more gems: the Cockaigne Overture,

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra,

Symphony No. 1 (in A flat major) –

Also Sea Pictures (to give you a flavour),

A superb song-cycle. Dame Janet Baker,

At her brilliant best, made these songs her own,

With her rich, mellifluous contralto tone.

Sir Edward’s modesty was impressive:

“I ask for no reward, only to live

“And hear my music.” It’s not recorded,

But I hope that he was well rewarded.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

“The two bloodiest battles ever fought

“On earth.” So Lloyd George described the onslaught

On the Somme, and the ruinous defence

Of Verdun, in his Memoirs. No pretence

Did he make of the cost, which was immense.

Over 300,000 of the best,

The bravest, as both sides rose to the test,

Died on the Somme. The huge losses sustained,

For no significant advantage gained,

“Were not only heavy,” reports explained,*

“But irreplaceable”. The allies,

Badly wrong-footed, were cut down to size

By the enemy assault on Verdun.

The great Somme offensive should have begun

In the spring. With the Germans on the run,

The allies could have broken through. Job done.

It was not to be. The French commitment

To Verdun’s defence meant, in the event,

That the British had to extend their share

Of the line. Haig, all too well aware

Of the risks, sought to delay the attack.

Joffre was insistent. To put it back,

As Haig would have liked, was not (repeat, not)

In the allied interest. A grim lot,

The French. Who cared how many British died?

Haig, out of a sense of mistaken pride,

And egged on by the British High Command

(Viz. Kitchener), succumbed to the demand.

So it was that on the 1st of July

The Brits went over the top. Why, oh why,

One wonders, did so many have to die?

With no major strategic objective,

The attack was doomed. It’s hard to forgive.

The great offensive would prove decisive,

So the troops were told. This, of course, was lies.

These volunteers were in for a surprise –

‘Kitchener’s Army’, so-called. Remember

The recruits, from August to December,

1914, who had signed up to serve,

Patriots all? It took a mighty nerve

To subject these untested young heroes

To such a bloodbath as the Somme. Who knows

What would have happened had we just stayed put,

Instead of inching forward, foot by foot,

To win, at very most, ten miles of ground

Over four long months. The numbers astound:

Over 600,000 missing, dead

Or wounded from the allies, with (I’ve read)

Some half a million Germans to boot.

Yet your average British raw recruit

Was assured it would be a piece of cake.

The Battle of the Somme was make or break,

And the trusty Tommy, for pity’s sake,

Would rise to the challenge and win the war.

A crack at the Boche! Well worth waiting for!

Heavy bombardment was the British ploy,

Over five long days, designed to destroy

The German line. It managed to annoy,

To harass (little more), the enemy

In their trenches. The Germans, patently,

Got the message, only too well aware

Of an imminent attack! I despair.

The British guns, moreover, were unfit

To do the job. Only a direct hit

Would cause any real damage, alas,

To the barbed wire, that murderous mass

Of ghastly, twisted metal – a death trap

For poor Tommy Atkins, wretched young chap.

On the morning of the 1st of July,

“Over the top!” was the rallying cry –

To do or die. The Germans were ready:

Their guns were prepared; their nerve was steady;

They had little to do but watch and wait.

The infantrymen stepped up to the plate.

When the call came they didn’t hesitate.

For reasons I find hard to understand,

They were expected to cross No Man’s Land

Weighed down with equipment (sixty-six pounds,

Supplies and shovels, the folly astounds:

That’s the weight of two heavy suitcases).

To cross a battlefield, of all places,

With such a handicap, was plain barmy.

Madness. What a way to treat an army.

Haig was sure of an easy victory,

So confident, and complacent, was he

That bombardment by the artillery

Would deal a death blow to the enemy.

All the soldiers would then have to do,

In his smug, over-optimistic view,

Was fortify the line. Crazy, but true.

“The wire has never been so well cut,”

Haig insisted. Sadly, anything but.

The men were not equipped for an assault,

And this was largely the General’s fault –

A hideous, monumental blunder.

Would things have been different, I wonder,

Had Sir Douglas, for his pains, been aware

Of the facts? I doubt it, and I despair.

Be that as it may. For ‘devil-may-care’

Was the mood of the day. Over they went:

Men with rifles, bayonets, equipment,

Field telephones, shovels and picks… God knows

How any survived at all, poor fellows.

Platoons of soldiers advanced in waves.

There are tens of thousands of unmarked graves

In No Man’s Land. Forward the front line surged,

As the German machine gunners emerged

And blasted the wretches to smithereens.

The Somme was the most murderous of scenes

In British military history.

It remains something of a mystery

Why commentators leap to the defence

Of Haig. The Somme offensive made no sense.

The soldiers had been trained to advance

In straight lines. Poor souls, they hadn’t a chance.

German machine guns fired at a rate

Of six hundred rounds a minute. Some fate.

The communication lines, I fear,

Were poor between the command, in the rear,

And the officers at the Front. The plan,

From the moment the first assault began,

Was to throw in men, on a massive scale,

In successive waves. It was sure to fail.

News of the slaughter did not trickle through,

Strange as this might seem, to Army HQ

Until early afternoon. Some delay!

Casualty figures on this first day

Were the worst for any day of the war:

Some 20,000 killed (probably more),

And 40,000 wounded – over half

Those who fought. Satan was having a laugh

On the Somme that day, no shadow of doubt.

Men from whole communities were wiped out

In half an hour. Recruits from one town,

Accrington, in Lancashire, were cut down

In droves: five hundred and eighty-four killed,

Wounded or missing, precious blood spilled,

All for nothing. There’s a most moving play,

A testament to the grief and dismay

Suffered by the town that terrible day,

When news of the great catastrophe broke.

A tale of strong, plain, ordinary folk,

The Accrington Pals takes us to the heart

Of this sad story from the very start.

Peter Whelan, a natural playwright,

Pitches the tragedy exactly right.

British newspapers could not have cared less

For the truth. “A good day,” boasted the press,

“For England!” The push was “sparing in lives”.

Can you believe it? The record survives.

Back to top / Buy the book