Volume Six – 1685 – 1688

James the Second, the Forgotten King

JAMES THE SECOND (1685 – 1688)

THE KING IS DEAD! LONG LIVE THE KING!

MONMOUTH’S REBELLION

CORONATION

WILLIAM OF ORANGE

ESCAPE TO FRANCE

JAMES THE SECOND (1685 – 1688)

King James the Second. What can I say?

The fool who threw his kingdom away.

He started well but, alackaday,

After four short years, in disarray,

He fled to France and called it a day.

A complex soul, it wasn’t James’ way

To compromise. To widespread dismay,

He sought to impose his will. Well, hey –

What use are subjects if not to obey?

Where Charles the Second learned to duck and dive

(Unlike his father) – thus staying alive –

His brother James inherited, in spades,

Their father’s intransigence. As young blades

They displayed similarities, of course.

Both were handsome, both looked good on a horse,

And both had an eye for the fairer sex

(That’s an understatement). Both risked their necks

In battle, though too young by far to fight

In the Civil War; and neither was that bright.

Yet, from quite an early age, James needed

Order and structure. He best succeeded

When required to follow clear sets of rules.

It’s said, as King, that he suffered no fools.

I take this as meaning (only my view)

That he hated surprise, anything new.

He enjoyed a brief, outstanding career

Under the great General Turenne. Here,

In the French army, were rules to obey,

Orders to follow. James liked it that way.

One of the major attractions, I’d say,

Of the Catholic Church (still to this day)

Is its disciplined structure, its ritual,

Its rites and strict sense of the spiritual –

Eagerly adopted as habitual

By the ever-devoted James. This passion

Caused his collapse in spectacular fashion

Back to top / Buy the book

THE KING IS DEAD! LONG LIVE THE KING!

When his brother Charles the Second breathed his last

(A sudden stroke), were Anglicans downcast?

Tories and Protestants, were they aghast?

Apparently not, strange as this might seem.

They welcomed King James as if in a dream.

A dreadful Papist, whom five years before

They’d set upon as rotten to the core

And sought to bar from his inheritance –

Foe to the Church of England, friend to France –

The country now embraced with a will.

It seemed, in faith, that Time had stood still.

In contrast to the late King’s negligence,

Intemperance and cool indifference

To hard graft stood the new King’s diligence,

Sobriety, economy, sound sense

And straight talking. Slender intelligence,

Backstairs debauchery, intransigence –

To say nothing of downright arrogance –

All were overlooked. It soon turned sour,

But James, for now the hero of the hour,

Denied a taste for arbitrary power.

King James confronted the issues head on.

Though never a man to be put upon,

He published for the ‘education’

Of his people, this declaration

To his Council: it would be his “endeavour”

(I do have to say, the wording was clever)

“To preserve this government in Church and State

“As it is by law established”. Far too late

Did Englishmen discover (a bitter pill)

This warranty to be far from James’ true will.

His words, let us say, were ‘conditional’.

Be that as it may, the King (for good or ill)

Would take all due care to “defend and support”

The Church of England. This was to come to nought,

After many a battle fiercely fought,

But for now men rejoiced. They swallowed it all,

Hook, line and sinker. James’ precipitous fall

Is unparalleled in English history,

His character to blame (no great mystery).

I’ve no doubt at all that he meant what he said.

Within four years, however, the King had fled –

Over the water to France. England’s Great Seal

He dropped in the Thames. It hardly seems real.

Part of the new King’s initial appeal

Lay in his ‘difference’. His elder brother

Was a law unto himself, like no other.

James was transparent, completely straightforward.

Loyal subjects need fear nothing untoward.

From the declaration quoted above,

It’s plain James expected deference – nay, love.

This was his due. As King he would persever

To defend the right of the Crown, but never

“Invade any man’s property”, ever.

Who, after that, could fear this Catholic King?

Church and State James would preserve – everything.

He meant not a word of it. Sickening.

Even as England’s pulse was quickening,

James was planning a papist takeover –

No cursory Catholic makeover,

But a sea-change in the nation’s affairs.

Protestants had been taken unawares,

Tories and Anglicans, duped to a man.

It wasn’t that long before the fun began.

All that’s to come. Our friend, John Evelyn,

Welcomed the new era James ushered in,

The King “affecting neither profaneness

“Nor buffoonery”. John favoured plainness

And morality over idle sport,

Noting, early, “the face of the whole Court

“Exceedingly changed”. The late King, indeed,

Was “obscurely buried” (sinners take heed)

“Without any manner of pomp”. Rotten,

In my view, that Charles was “soon forgotten”.

“Everything is very happy here,”

Wrote the Earl of Peterborough. “Hear, hear!”

They chimed. Such was the general refrain.

“I doubt not but to see a happy reign.”

Back to top / Buy the book

MONMOUTH’S REBELLION

One stroke of luck gave James an early boost.

You’ve heard of chickens coming home to roost –

Well, James, Duke of Monmouth, the King’s nephew,

Was shortly to cause a rare old to-do

By mustering a scratch invasion force

To challenge his uncle. Crazy, of course.

His strategy and timing were all wrong.

The new monarch, as we’ve seen, was ‘on song’

And commanded the heights (if not for long).

Monmouth fully expected folk to rise

In defence of his ‘right’. Surprise, surprise:

When he landed his paltry force at Lyme

(Eighty ‘troops’, a handful of boats), his crime

Was palpable. Rebellion – no more,

No less. You could barely call it a war.

Pathetic. An amateur indulgence.

His claim to the throne? Pure, idle nonsense.

The Duke’s aims were over-ambitious,

Foolhardy, vain and injudicious.

He hoped (or somehow was led to expect)

The English army, in droves, to defect.

Thousands of rough yokels flocked to the cause

Of the ‘Pretender’. Since the Civil Wars

The West Country had been strong in support

Of non-conformity. Their last resort

Was rebellion, but they weren’t the sort,

These sons of the soil, to band together

Into a fighting force. Who knows whether,

Had he stuck to his guns, the wretched Duke

Might just have made it… He earned the rebuke

Of his supporters by losing his nerve.

They’d hailed him King (which he didn’t deserve)

And, armed to the teeth with sickles and scythes,

Declared for Monmouth. Distinctly unwise.

The honest labourers of Somerset,

The ploughboys of Devon and West Dorset,

Paid a painfully heavy price, poor sods.

They went like lambs to the slaughter. Ye gods!

Monmouth led his rabble of an army

Towards Bristol. It would have been barmy

To march on London (at this stage, at least) –

Anywhere, frankly, towards the south-east –

But Bristol was feebly fortified

And rich with sympathisers. Had he tried,

Our friend might well have taken the city

With comparative ease. More’s the pity

(From a rebel point of view), he funked it,

Withdrawing to Bridgwater. Did he quit?

No. Though Monmouth’s confidence, bit by bit,

Ebbed away as the King’s forces closed in,

He dreamt nonetheless that still he could win –

Given some luck and a following wind.

He was anything if not determined,

Resolving to launch an assault, by night,

At Sedgemoor. Now, if I’ve got my sums right,

The rebels still outnumbered James’ forces –

In men, at least (not sure about horses).

Under cover of dark a surprise attack

Could scatter the enemy. No going back.

The King’s troops had just settled in for the night

When a rather jumpy rebel took fright

And fired his trusty musket by mistake.

James’ men (still half-asleep for pity’s sake)

Seized their weapons, though fearfully prepared

For sudden, violent death. Most were spared.

For Monmouth’s wretched rag-bag, sad to say,

Had left their maps at home. They lost their way,

Stranded on open ground. At break of day

All were exposed as sitting ducks. Well, hey –

They learnt their lesson: never to rebel

Against the Lord’s anointed. Truth to tell,

Those who missed being felled by musket fire,

Or hacked to death with swords, were to aspire

To a fate more awful, deadlier by far,

At the Bloody Assizes. An abattoir

The West Country resembled, as ‘justice’

(Ha!) was wrought on the insurgents. Mark this:

Dozens of poor peasants were hanged or shot

Without a hearing. James, like it or not,

Sanctioned this outrage. The King was advised –

By Chief Justice Jeffreys (few were surprised) –

That those who’d proclaimed his nephew as King

Could be hanged without trial. A dreadful thing.

This would act “as a terror to the rest”.

King James agreed. I venture to suggest,

If Kings can’t be fair they should try their best.

Well, James comprehensively failed the test.

The Bloody Assizes (so-called) were worse.

Justice? Jest not! This was quite the reverse.

The Lord Chief Justice gave good cause to curse.

Jeffreys and his cronies, mere acolytes,

Rode roughshod over fairness, human rights

(As we’d call them today) and due process.

They were out to convict, no more, no less.

The sad victims of these treason trials

Were afforded no say, no denials,

No defence. Jeffrey’s victims, by the score –

Two hundred, three hundred, possibly more –

Were executed by hanging, drawing

(I’ll explain that shortly) and quartering.

Imagine anything more eye-watering.

Preparations for the awful slaughter

Were precisely drawn: the boiling water

(Salted, for the better preservation

Of the heads); axes (for separation

Of the said quarters); the gallows, of course;

Oxen to draw the carts (or the odd horse);

Tar (in copious quantities); sharp pikes

(On which to display the severed heads); spikes

And knives (with which to gouge the entrails out):

A costly undertaking, have no doubt.

“Enough!” the sensitive among you cry.

“What of the Duke?” you ask, the reason why

So many noble peasants had to die –

Monmouth the brave, the handsome! Sad to say,

The coward took to horse and rode away.

The ‘darling of the people’, Monmouth fled,

Dumped on his followers, left them for dead.

I’m relieved to say, he too lost his head.

King Charles the Second’s eldest bastard son

Was a lightweight varlet, all said and done.

Within three days of the rout at Sedgemoor

He was found in a ditch. Need I say more?

Dishevelled, famished, “ ’tis said he trembled” –

Evelyn’s expression. He resembled

A scruffy rustic, with a rough grey beard.

It was Uncle Jimmy whom now he feared.

He found the King in no forgiving mood.

He’d called James a usurper (pretty rude),

Even hinting he murdered his brother,

King Charles. What with one thing and another

(Responsibility for the Great Fire

Included: Monmouth was such a fine liar),

It comes as no surprise that the Duke’s pleas

Fell on deaf ears. Monmouth dropped to his knees,

Begging, pleading, as he’d done in times past

Before Charles, his pa. These tears were his last.

His cries were in vain. James’ mind was made up.

His slimy nephew, this infamous pup,

Paid dear for his treachery. And that’s why,

In ’85, the 15th of July,

The Duke was despatched to the block – to die!

Back to top / Buy the book

CORONATION

King James declined to take the sacrament

At his Coronation. To what extent

This neglect gave rise to hostile comment

Among Anglicans one can only guess.

It appears he simply couldn’t care less.

Indeed, the scoundrel celebrated Mass

Just hours before he was crowned. Silly ass:

Clumsy, insensitive, wilful and crass.

He’d already pledged to Parliament,

Hypocrite as he was, his firm intent

To preserve, in essence, “this government

“In Church and State”. To this laudable end

He would strain every sinew to defend

The Church of England. Anglicans rejoiced.

What the new King, however, scarcely voiced

Was his parallel determination

To show indulgence and toleration

Towards Catholics. James’ reputation

As a staunch Papist had split the nation

During the Exclusion crisis. Now –

Who knows why or wherefore, but anyhow –

Men were prepared to take James at his word

When he pledged to support the Church. Absurd.

At his Coronation the worst occurred,

Raising some eyebrows. The crown slipped off his head.

The most ill of omens, it has to be said.

The King resolved to promote the interests

Of Catholics by dispensing with the ‘Tests’.

Papists suffered a manifest injustice,

Barred, as they were, from political office.

James viewed monarchy as a sacred service –

God’s work. The sweeping away of prejudice

Was right and just. It’s hard to argue with this.

James was the model of a progressive King,

A ‘modern’ monarch. He lacked only one thing:

An instinct for the ‘art of the possible’.

For James considered himself unstoppable.

First, he urged his Parliament to repeal

The penal laws. Who couldn’t see the appeal

Of tolerance for Catholics? Then (phase two),

Repeal of the Test Acts. You’d think, wouldn’t you,

That James might have foreseen the naked terror

That seized his subjects. A serious error.

However illogical their dread might be,

They feared that the papist constituency,

Delivered from their religious fetters,

Would swiftly supplant their Protestant ‘betters’,

Propelling an unsuspecting nation back

To Queen ‘bloody’ Mary’s reign. Thumbscrews, the rack,

The stake… Anglicans had an uncanny knack

Of demonising the anti-Christ, the Pope.

Rumour, fancy and lies. James hadn’t a hope.

Back to top / Buy the book

WILLIAM OF ORANGE

William of Orange, James’ son-in-law,

Had for some years been preparing for war –

Well, ‘invasion’. The Prince was wary

Of saying ‘war’. Opinions vary,

But had Will, it’s generally reckoned,

Declared open war on James the Second

(His uncle too), then disaster beckoned.

How long he’d coveted the English throne,

If indeed he had, is largely unknown.

But the Prince did express himself willing,

If invited, to accept ‘top billing’ –

To set the poor repressed of England free

From despotism and from popery.

The Prince did not have to wait long. Six peers

And one ex-bishop (inspired, it appears,

By James’ conduct and the birth of an heir)

Had written to William, then and there,

Inviting him to bring over a force

To England against the King. Now, of course,

The letter was couched with enormous care,

The signatories all too well aware

Of the danger of their position.

They neither sought James’ deposition

(Not openly) nor his exclusion –

Even if this was the conclusion

Likely to be drawn. Seven men, and yet

None the highest in the land. You can bet

That William was nervous. He is said,

Indeed, to have spoken of his deep dread

And terrible disquiet. Nonetheless,

Here was a letter. He had to confess

That this frank and open demonstration

Of support, this overt invitation

From a broad cross-section of the nation,

Gave succour to his hopes. For some months past,

Others, with their numbers increasing fast,

Had ‘intimated’ (no stronger than that)

They’d be more than happy to ‘have a chat’

With the Prince should ever the need arise.

Halifax was one such (this no surprise),

John Churchill (James’ favourite) another,

Clarendon (Rochester’s elder brother),

And even Rochester himself, we’re told.

Stout chaps – never knowingly undersold!

There was now every indication

That the greater body of the nation

Would rally to Will’s support. There were fears

Among the people, of course. Three short years

Since, Monmouth’s rising had ended in tears –

Rebel corpses hung from every tree

The whole length and breadth of the West Country.

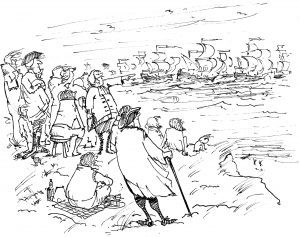

William’s plans were reaching fruition.

Focused, resolved, a man on a mission,

The Prince was ready. His invasion fleet

Comprised some sixty warships (no mean feat),

With 15,000 soldiers – infantry

(Eighteen battalions), and cavalry

(Over 4,000). Think of the horses!

All the supplies required for these forces!

Food, uniforms, guns, brandy, tobacco –

Even salted herrings, I’ll have you know;

Medicines, hay for the horses, new boots –

Though few, I’ve been assured, were raw recruits;

Printing presses, too. For the Prince, you see,

Declared himself, with blushing modesty,

The champion of English liberty.

It’s likely the Prince intended to land

In Yorkshire. These things rarely go as planned.

All depends on the wind, you understand.

If it suddenly switches to the east –

And wind can be a pretty fickle beast –

Attend to its dictates and change tack fast.

An easterly breeze? Will wasn’t aghast.

He seized the opportunity, at last,

To sail with ease through the Straits of Dover,

Then west down the Channel – a walkover.

The Dutch armada was a splendid sight.

You could stand on shore (the weather was bright)

And watch the famous flotilla sail past

For seven whole hours, from first to last.

The King left London for Salisbury.

There his nerve deserted him. Treachery,

Alas, within the ranks of his army

Sapped his spirit. In the midlands, Derby

Declared for the Prince, then Nottingham too.

James swithered and dithered. What should he do?

The Earl of Danby took control of York,

Proof (once again) that he wasn’t all talk.

Most of the north was for Orange, it seemed.

As his surly subjects plotted and schemed,

The King suffered a collapse. A martyr

To nosebleeds, battle was a non-starter.

He withdrew to his room for hours on end,

Nursing his hooter. His most sure friend

Deserted: John Churchill, his protégé,

His sworn brother-in-arms in exile, nay,

His page (at the tender age of sixteen),

His age-old chum and confidant. Obscene.

James turned tail. With only one end in sight

He was now resolved, determined on flight.

Had he changed his mind and opted to fight,

The odds are he would have been trounced. And yet,

He’d have won some compassion – you bet!

William, you’ll recall, was adamant

That he didn’t come for the crown. Pure cant,

Of course, but poor James, by fleeing the land,

Strengthened the Prince’s already strong hand.

Negotiation would have been far worse

For William. It might have seemed perverse

To meet his stricken uncle face to face

And quibble over terms. Will knew his place:

Watch and wait. The throne was the King’s to lose.

The Prince kept his cool. He would let James choose.

Back to top / Buy the book>

ESCAPE TO FRANCE

With the Duke of Berwick, his bastard son,

James stole away by night. The deed was done.

They took a rowing boat down the Medway,

Then a ship to France. Now an émigré,

The King landed en France on Christmas Day.

Dashed hopes and decrepitude, sad to say,

Were old James’ destiny, death and decay.

The Prince of Orange was victorious –

His ‘Revolution’ dubbed ‘Glorious’.

Courageous, resolute and strong-willed,

Was William’s early promise fulfilled?

We shall see. His military campaigns,

Alas, led to few significant gains.

His was a disappointing legacy,

All said and done. The Stuart dynasty

Died out with Queen Anne. Hers was the glory –

But that, as they say, is another story.

Back to top / Buy the book