Volume Fifteen – 1939 – 1945

The Second World War

GAS MASKS AND THE BLACKOUT

EVACUEES

DUNKIRK

FRENCH COMPLACENCY

THE BLITZ

THE JAPANESE BOMBING OF PEARL HARBOUR

‘GERMANY FIRST’

MONTY’S CHARACTER

VERA LYNN

THE BOMBING OF COLOGNE

HITLER PREPARES FOR THE END

VE DAY

GAS MASKS AND THE BLACKOUT

Although everyone was braced for war,

Nothing very much happened for two, four,

Six… no, eight months. However, ‘be prepared’

Was the message. At first, people were scared.

They all carried their gas masks in the street,

In cardboard containers, all very neat.

Some kids had Mickey Mouse ones, rather sweet.

The hospitals were cleared, every bed

Kept free for victims of air raids instead.

Theatres and cinemas closed their doors,

By order. There was rapturous applause

When they welcomed audiences again,

Just a few weeks later. A constant pain

Was the blackout. Show a mere chink of light,

The ARP were after you all right!

The shops quickly ran out of black fabric:

Old clothes and curtains had to do the trick.

Walking home at night was fraught with danger.

Pitch dark! Bumping into the odd stranger

Was a hazard, but there was worse than that:

Falling down steps, tripping over the cat,

Walking into canals, or through glass doors,

And tumbling over onto all fours.

One person in five sustained injury

In the blackout – crashing into a tree,

Or missing the kerb unexpectedly

And twisting an ankle. Seriously,

The risk was real. In September, we’re told,

Accidents on the roads increased twofold,

With twice as many people killed by cars

As in August. Even the twinkling stars

Were of little comfort. A tiny bit

Of light was permitted, a narrow slit

In a car’s front headlamps, but that was it.

The streets were still very dark and ill-lit.

Small hand torches were finally allowed

For pedestrians (bloody, but unbowed),

Dimmed by two layers of tissue paper

To minimise the beam. What a caper!

Sandbags protected public monuments,

Offices and government departments

From bomb damage. This made absolute sense –

Or would have done, except for the silence.

Balmy weather added to the pretence.

The people’s ‘carry on’ mentality

Was a sign either of their sanity

Or of wilful blindness. Banality?

Perhaps. Some lovers, on the other hand,

For reasons not that hard to understand,

‘Took the plunge’. Well, you have to live your life.

More engaged couples became man and wife

In those first few weeks than ever before,

As soon as they heard there would be a war.

The jewellers even ran out of rings,

Which now came off curtain rods, of all things.

Who knew what might happen? No time for tears.

They could be apart for months, if not years.

They would meet again, though who could say when?

Tens of thousands got married there and then.

EVACUEES

Others there were heading for the country.

Spare a thought for the poor evacuee.

Over three short days a mighty campaign

For mass evacuation, by train,

From Britain’s great cities was underway –

An incredible feat, I have to say.

Had the feared aerial bombing occurred,

The tragic loss of life, you have my word,

Would have been huge. Men, women and children,

Every law-abiding citizen,

Was at the gravest risk of being maimed,

Or worse. Millions of kids, it was claimed,

Were in danger. The expectation

Was that the planned evacuation –

Completely voluntary, by the way –

Would involve four million. Come the day,

About one and a half million went.

This comprised some forty-seven per cent

Of schoolchildren from the cities. Others

Included pregnant women and mothers

With children under five. Older children

Travelled unaccompanied, Bill and Ben

(Siblings, perhaps?) or, on her tod, wee Bren.

When I say ‘travelled unaccompanied’,

A few adults went with them, in a bid

To check things didn’t go wholly awry –

Not always with success, but worth a try.

As the trains pulled out of the termini,

Mothers wept. The thought of waving goodbye

(For how long?) was more than many could bear.

The children were travelling… who knew where?

Clutching their gas masks, sandwiches perhaps

(The lucky ones), but certainly no maps,

They had luggage labels with their names on.

Many of the poor souls were woebegone,

With tears streaming down their little faces.

Only a few had bags or suitcases,

Warm clothes for the winter, shoes with laces,

Or the faintest idea what lay in store.

After four long months of the phoney war,

By January, with no bombs falling,

The strain on families was appalling.

Over one million evacuees

Returned home. The majority of these

Remained in the cities throughout the Blitz.

Evacuation had been the pits.

Yet many evacuees, those who stayed,

Had a great time. They were far from dismayed.

Cows, they found, were bigger than dogs! They played

In green fields. What was this? A real bed?

Upon arrival, some had crept, instead,

Into a bottom drawer to go to sleep,

As they used to at home. You want to weep.

Some had never cleaned their teeth in their lives,

Or run hot water. The record survives:

Flannels, clean sheets, pillows… all alien

To these poor, underprivileged children.

There were endless cases of bed-wetting –

Needless to say, extremely upsetting.

For many evacuees were nervous

And unhappy (as well as verminous).

To their hosts, the level of poverty

They witnessed for the first time, properly,

Came as a profound and unwelcome shock.

Their social consciences took a knock –

Those who were sensitive enough, that is.

The whole affair was a dreadful business,

An eye-opener, they came to see that.

This did long-term good or I’ll eat my hat.

Even the Prime Minister, Chamberlain,

Expressed his horror. With a war to win,

There was little that could be done right now,

But folk sat up and took notice, and how.

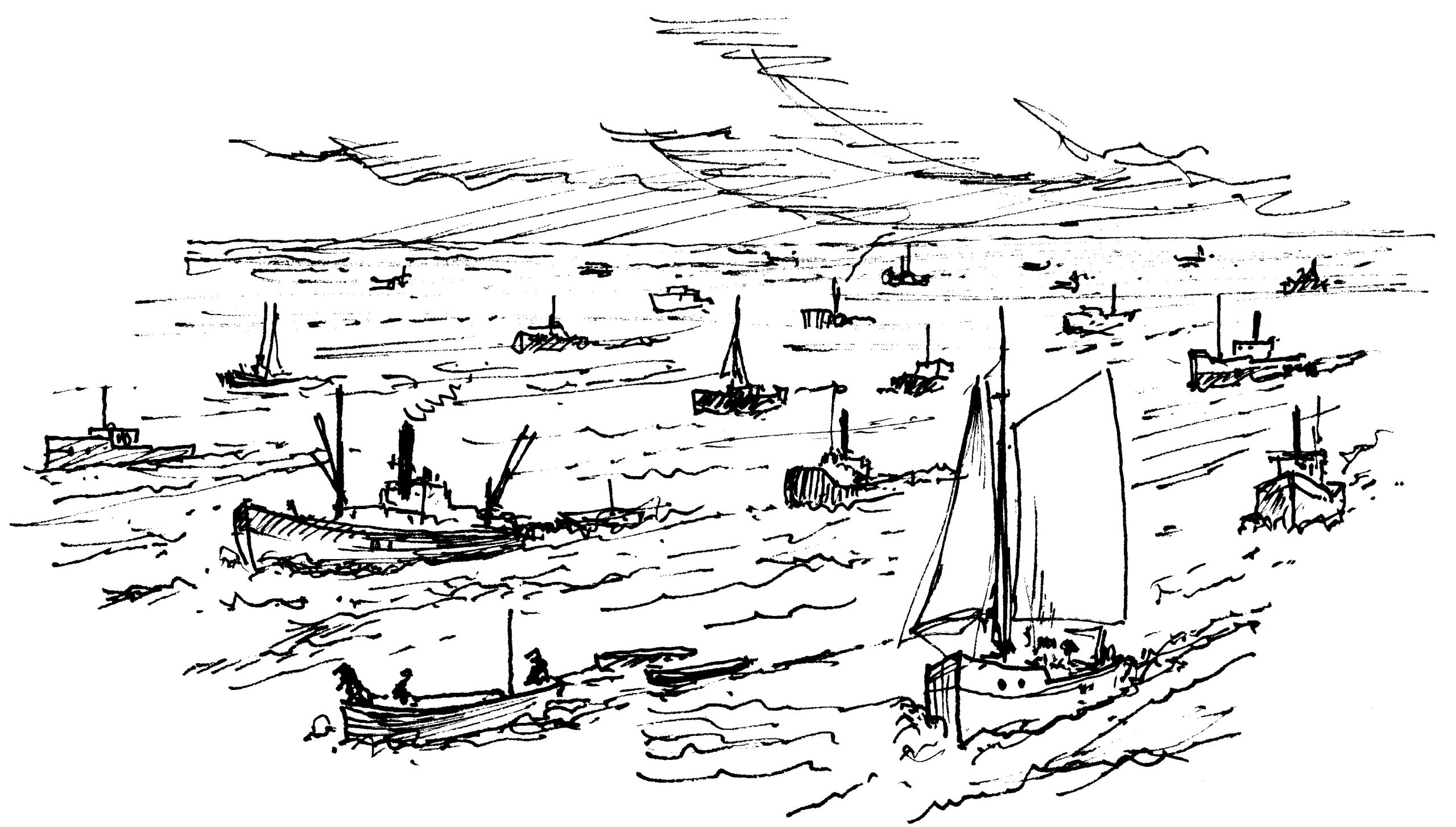

DUNKIRK

For the BEF, General Lord Gort –

A solid, unimaginative sort,

But able and practical nonetheless –

Was confronted with the most ghastly mess.

Gort was sure, by the 25th of May,

That France was putting up a poor display

Of resistance. Weygand’s counterattack

(Such as it was) was failing to hold back

The Nazi assault. Orders Gort received

To return south left him mightily peeved.

The chances of Arras being relieved,

Or Amiens, come to that, were so slim

That he refused to obey. Good for him!

Instead, the General stuck his neck out.

He knew the BEF without a doubt –

If they sought to do France’s dirty work –

Would be massacred. Cut off at Dunkirk,

His sole option was to put to sea

And to evacuate. It seems to me

That the General, single-handedly,

Discharged a rare responsibility.

As early as the 26th of May,

The withdrawal began. We know, today,

That the total number of troops rescued,

And saved from lifelong German servitude

(Or worse), numbered 200,000 Brits

And more than half as many French. Pickets,

Paddle steamers, fishing boats and dinghies

Backed up the Royal Navy. It was these,

And their valiant crews, that pulled it off.

Hermann Göring, for once, incurred the wrath

Of Hitler. Göring had assured his boss

That Gort’s forces would be trounced, without loss,

By the Luftwaffe alone. Well, not so.

Churchill knew that Dunkirk was touch and go.

Code-named ‘Operation Dynamo’,

He warned the Commons (and the nation)

Not to have any expectation

That the proposed evacuation

Would bring more than ten thousand to safety.

No one was more realistic than he:

Members should prepare for very bad news.

Dunkirk was the mother of all rescues.

A variety of factors combined

To avert disaster. Hitler, you’ll find,

Made a grave error (from his point of view)

In his French campaign, one of very few.

He feared a weakness on his southern flank,

Viz. a challenge from the French, tank for tank,

Should he push further into northern France.

A temporary halt to the advance

Was ordered. Gerd von Rundstedt had seen fit

To press the Führer to sanction it.

Hitler, though it stuck in his throat, agreed.

So, the allied withdrawal could proceed

With greater confidence. The Brits had need

Of a breather and for once they got it.

Hitler, it seems, did little to stop it.

He relied on Göring’s reckless promise

That the Luftwaffe (optimistic this)

Could wreak havoc on the allied units

Stranded at Dunkirk in north-eastern France.

The BEF now had a fighting chance.

The RAF, flying from home bases,

Put the Nazi bombers through their paces,

Inflicting some heavy casualties.

But the fight was far from being a breeze.

Evacuation came at a cost:

Nearly two hundred fighter planes were lost;

Six Royal Navy destroyers were sunk

And nineteen damaged – a sizeable chunk

Of the British air and naval defence.

Churchill, ever the voice of common sense,

Was of course relieved. He made no pretence,

However, that this was a victory.

Of all the withdrawals in history,

Dunkirk was the boldest, all said and done.

But the PM was clear: “Wars are not won”

(He was right) “by evacuations.”

Dunkirk was one of those occasions

When benign forces all came together.

The Channel was a mill-pond. The weather

Was perfect. To their eternal credit,

The brave Belgians fought on with spirit,

Their beleaguered forces doing their bit,

As even Hitler was forced to admit.

The most astonishing aspect of all

Was the way the British answered the call.

An urgent appeal on the BBC

Led to volunteers putting to sea

In any vessel that was fit to float:

Cabin cruisers, yachts, the odd rowing boat,

River launches… The flotilla numbered

(Light craft and the like) over eight hundred.

The Royal Navy too turned up in force

And was largely responsible, of course,

For the majority of those rescued.

But it was the ‘weekend sailors’ who crewed

This scratch armada, these gallant heroes,

Who, I’m pleased to say, got up Hitler’s nose.

The news, as Churchill knew, was less than good.

The BEF, it should be understood,

Left all their guns and vehicles behind.

Many British soldiers were resigned

To a grim life as prisoners of war:

Some 50,000 poor victims or more.

In the early French campaign, as a whole,

Some 68,000, a fearful toll,

From the BEF, were casualties.

It is terrible figures such as these

That remind us of the realities

Of warfare, the sacrifice and the pain.

Pray God it may never happen again.

FRENCH COMPLACENCY

The French were hardly covered in glory.

Complacency had ruled the roost for years.

Parisians could not believe their ears

When the news broke. The Nazis on their way?

Impossible, on such a sunny day!

According to Maurice Chevalier,

“Paris sera toujours Paris!” The song

Would offer them comfort. How very wrong.

The French government had strung them along:

France was safe behind the Maginot Line,

So no need to panic. All would be fine.

They now fled the capital in despair.

The roads were blocked. Terror everywhere.

Young and old, nuns and priests, all took their chance.

It’s calculated that in northern France

Over ten million were on the move.

To keep catastrophe at one remove,

That was their thinking, but what did it prove?

Nothing. Few folk knew where they were going.

What of the future? No way of knowing.

The poor suffered the most, always the case,

While the rich had wheels. A perfect disgrace.

The German fighters strafed them from the air,

Women, with their babes in arms. Cue, despair.

On the 14th, the Nazis occupied

Paris. Five short weeks (you’ll be horrified)

It took the German army to achieve

What in the Great War, it’s hard to believe,

Had proved impossible in four long years.

Now, tragically, the blood, toil and tears

Of that dreadful conflict had gone to waste.

An Armistice was not to Reynaud’s taste.

He resigned his office, a broken man,

And France (quelle horreur!) was left to Pétain.

You’d hardly call it a negotiation,

But Pétain agreed to the occupation

Of northern and western France – including the coast

From Belgium round to Spain and, what mattered most,

Paris. The southern part of the country

Would be ‘governed’ by Pétain from Vichy.

This, in effect, became a puppet state.

Collaboration, at any rate,

Saved Pétain’s bacon. The old man was free

To exercise civil authority,

Under Nazi auspices, from Vichy.

All France’s colonies, amazingly,

Followed suit. Game, set and match to Germany.

One solitary figure, Charles de Gaulle,

Decamped to England. To the shame of all,

When he urged the French, against all the odds,

To resist, only a handful (ye gods!)

Rallied to his standard. He kept alive

The hopes of the Free French. France would survive.

THE BLITZ

Britain’s fighter pilots were powerless

Against the night bombers. It was hopeless

To pretend otherwise. During the Blitz,

A citizen could be blown to bits,

And his house, in a matter of minutes.

The Luftwaffe’s random, but lethal hits

Caused, by the end of this first awful year,

Twenty-three thousand deaths, with more, I fear,

The next, right through to the middle of May.

It was recently I read with dismay

That more civilians died in the war

Than combatants (a lamentable score)

Up to September, 1941.

And for each victim (yes, every one),

Thirty-five, at least, were rendered homeless.

It really was a most terrible mess:

Three and a half million homes destroyed.

Londoners were far from overjoyed

On the 29th of December.

The Great Fire of London, remember,

Was in 1666 – the last one,

That is. Here was another. Poor London!

Incendiaries set the City ablaze.

One image, which will forever amaze,

Was that of St. Paul’s in the midst of it,

Missing, by a whisker, a direct hit.

A miracle. Christopher Wren’s spirit

Was surely at work here. Good for Sir Kit!

Some fifteen hundred fires blazed that night.

The great conflagration burned so bright,

The glow could be seen sixty miles away.

The fire fighters were fit for the fray,

But ran out of water. The Thames, alas,

Was at its lowest ebb. One fiery mass

Was the City, as it was left to burn.

Arthur Harris was watching with concern,

Or Air Marshal ‘Bomber’ Harris to you.

“Well, they are sowing the wind” (sadly true),

He observed. The citizens of Dresden,

And of Hamburg, would reap it, as and when.

In excess of twenty-five thousand died

In Dresden. Those who take Harris’s side…

Well, I’ve my view… I’ll leave you to decide.

Those poor souls who perished in the City

Numbered just one hundred and sixty-three –

There were so few residences, you see.

For every death we should show pity.

To reduce it to the nitty-gritty,

However, there can be no comparison

Between the sickening bombing of Dresden

And what occurred in the City that night,

Whatever the victims’ harrowing plight.

THE JAPANESE BOMBING OF PEARL HARBOUR

The course of history changed when the Japanese

Bombed the American fleet, with apparent ease,

At Pearl Harbour on the 7th of December,

A Sunday the US will ever remember.

Pearl Harbour was open to attack: aircraft

Parked on the runways (how the Japanese laughed);

Battleships in harbour, mostly understaffed,

All sitting targets; the anti-aircraft guns

Locked and unmanned. The fault must have been someone’s.

How could a navy have been so unprepared?

The Japanese triumphed. The US despaired.

Terrible carnage. A vision of hell.

More than three and a half thousand personnel

Were killed or seriously injured that day,

Most of them combatants. It’s hard to convey

The full extent of the devastation:

Four battleships sunk (an aberration);

Four severely damaged; ten more men-of-war

Put out of action; and (this I deplore)

Three hundred and fifty US aircraft lost.

The disaster was at very little cost

To the Japanese. They lost twenty-nine planes

And not one of their fleet, which perhaps explains

Why Pearl Harbour has gone down in history

As a famous military victory

For the Japanese and a catastrophe,

On an epic scale, for the US navy.

Yet it could have been far worse had it not been

For one fortunate circumstance, unforeseen

By the Japanese. For away, on repair,

Or on exercise (a miracle, I swear),

Were all four aircraft carriers, a nightmare,

Otherwise, for the whole American fleet.

The Japanese success was thus incomplete.

As the US navy got back on its feet,

It was far from business as usual –

But their aircraft carriers proved crucial.

‘GERMANY FIRST’

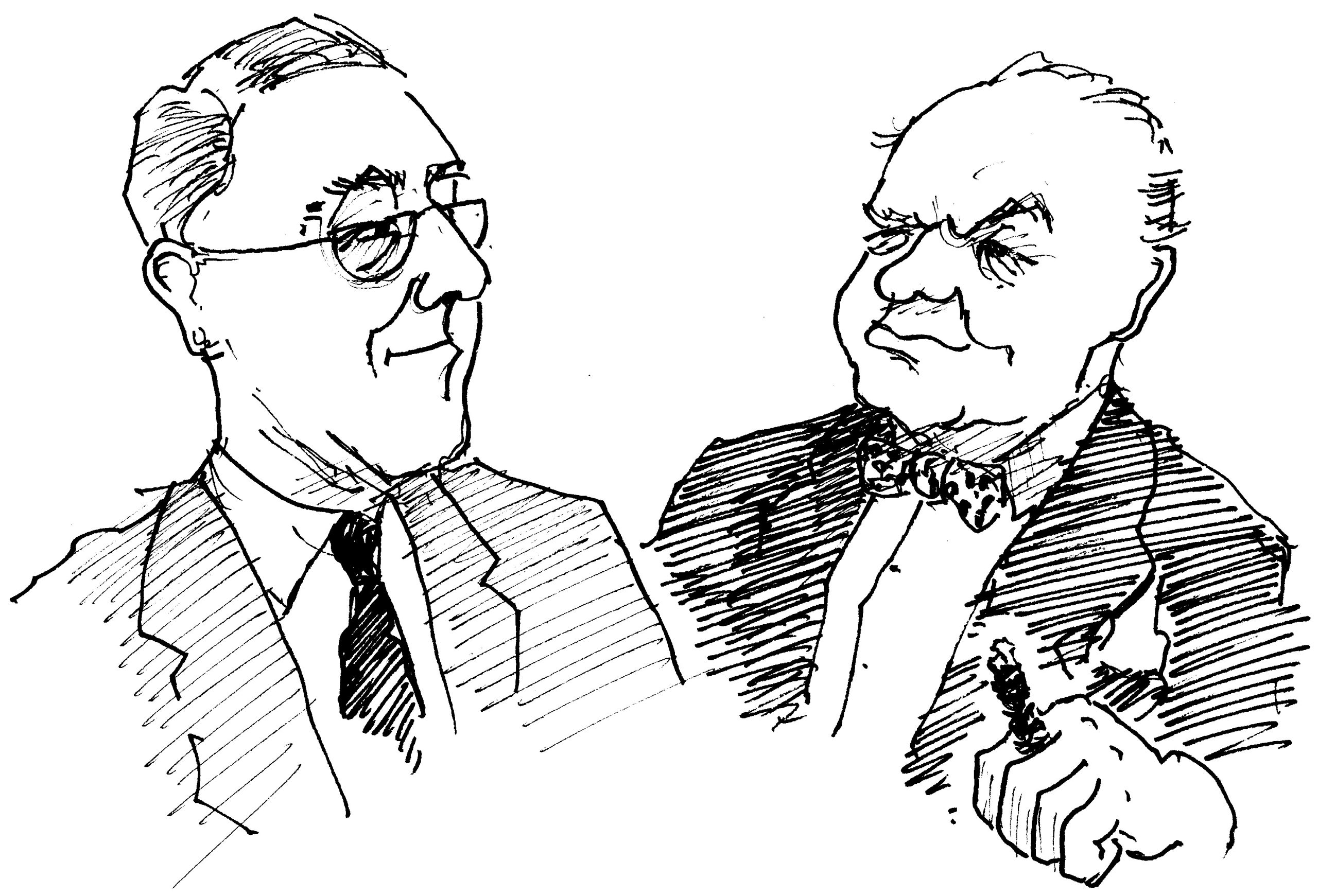

Churchill and Roosevelt were in their prime.

The British Prime Minister lost no time.

He set sail on the 12th of December –

Five days after Pearl Harbour, remember –

And was met in person by Roosevelt.

As for Churchill, you wonder how he felt

As he took hold of Roosevelt’s “strong hand,

“With comfort and pleasure”. Though far from grand,

The President’s manner, you understand,

Was impeccable. Churchill was to stay,

As his guest, at the White House. Some dismay

This caused Churchill at first. What do you think?

The Roosevelts were stingy with the drink –

So at least the Prime Minister had heard.

Imagine anything quite so absurd.

Churchill’s needs were fully attended to,

Including his taste for alcohol. Phew!

Both Houses of Congress on Boxing Day –

This was an official holiday;

Who cared? – gave him a rousing reception,

Cheered to the rooftops, without exception.

His anti-German remarks were received,

The ever-sensitive Churchill perceived,

With less enthusiasm, he believed,

Than his anti-Japanese comments. Well,

No matter. They all got along just swell.

So, ‘Germany first’. But what did this mean?

Pearl Harbour had been largely unforeseen.

The Pacific was a naval affair.

The army needed a focus, but where?

In due course there would be occasion

For a European invasion

From England across the Channel, you bet,

But that would take time. Certainly not yet.

So the Americans gave the green light

To the North African campaign, a fight

They would join sometime in ’42,

Codenamed ‘Operation Torch’. Who knew,

At this early stage, what that would lead to?

Roosevelt had to build up his army, too.

But Churchill had won FDR’s consent,

In principle, so he was well content.

Next, the Canadian Parliament.

His speech was a corker! Some years before,

The French (who Churchill preferred to ignore)

Predicted that Britain, an utter wreck,

Would collapse within three short weeks, “her neck

“Wrung like a chicken”. You wonder they dared.

A lesser orator might have despaired –

Not Churchill. “Some chicken!” (a pregnant pause,

Impeccably timed) “Some neck!” Cue, applause.

MONTY’S CHARACTER

Monty for his part was up for a fight.

Hyperactive and formidably bright,

And the most brilliant of strategists,

He suffered neither fools nor conformists.

A short man, with a beaky little nose,

Who ‘fluffed’ his r’s (endearing, I suppose),

Abrupt or polite as the need arose,

It was Monty’s eccentric little ways

That marked him out. Regimental berets,

With a wide array of badges, he wore;

His informal dress you couldn’t ignore –

Floppy pullovers and old corduroys.

For Monty, you see, was one of the boys.

He had a huge ego. He was ruthless

And focused. His energy was boundless.

He was ever brimming with confidence.

His sense of self-importance was immense.

Yet he played the popularity card

For all it was worth and in this regard

He met his men face to face, working hard

To command their respect. This was to prove

Crucial. Morale began to improve,

Within days, under Monty’s leadership.

His officers were urged to “get a grip”.

Orders were orders. Contingency plans

For withdrawal were burnt, as Monty fans

Outnumbered the cynics by ten to one.

The battle ahead was as good as won.

Yet Montgomery did not hesitate

To watch, until the time was ripe, and wait.

Preparedness was the name of the game

And Monty’s 8th Army won lasting fame

Only after achieving victory

Once they were ready. It’s no mystery

How this was accomplished. Montgomery

Refused to be drawn by Rommel’s attacks.

A cautious response of ‘mind your backs’,

That was enough. Meanwhile a thousand tanks –

Shermans, for which Alexander gave thanks –

New from America, were on their way.

Monty left nothing to chance. To this day,

We should all salute his thorough approach,

Painstaking, careful and beyond reproach.

VERA LYNN

One ‘artiste’ prepared to travel as far

As Burma was that perennial star,

The ‘Forces’ Sweetheart’, songbird Vera Lynn.

With the voice of an angel, pencil-thin

And graceful to boot, with a war to win,

She understood that servicemen abroad

Were not only at risk of being bored,

But in danger, too, of feeling ignored.

So Vera did her bit. We’ll Meet Again,

Her most famous hit, a rousing refrain,

Was recorded in 1939.

It was hard graft, far from roses and wine,

Touring to these remote outposts of war.

To Egypt, India, Burma and more

Vera travelled. Boosting morale, for sure,

Was her mission. Back home (never a chore)

The popular star was happy to tour

To hospitals. Talking to new mothers,

She sent messages to husbands, brothers

And loved ones on her radio programme,

Sincerely Yours. From Cairo to Assam,

They tuned in to listen to Vera Lynn.

To ENSA. I’m not sure where to begin.

Battling with gusto through thick and thin,

They toured the world. The money was tight,

The talent ‘limited’: ‘Every Night

Something Awful’! This was a painful slight.

The Entertainments National Service

Association did not deserve this –

Well, not altogether. Stars of top rank

(Vera Lynn herself) had ENSA to thank

For sponsoring their tours. George Formby

Was another, with his ukulele.

Established stars such as Noël Coward

Joined Terry-Thomas and Frankie Howerd

From the ranks of the unknown (to date) –

A famous list of names, at any rate,

Whether current or for another day:

From Gracie Fields to Stanley Holloway;

From Peter Sellers to Kenneth Connor;

And from Jessie Matthews (who, good on her,

Loved to tour) to more lowly riff-raff.

For ENSA suffered (and you have to laff,

As wee Georgie might say) from a small pool

Of talent. Most of the acts, as a rule,

Were cobbled together and of low grade,

And a number quite smutty, I’m afraid.

Even the stars were pretty poorly paid,

But few really cared. Didn’t folk know

There was a war on? So, keep on the go,

That was the motto, and go with the flow.

The number of ENSA concerts given

Exceeded two and a half million

By the time the war was over. Not bad.

All in all, I’d say, a good time was had.

THE BOMBING OF COLOGNE

On May the 30th, a calm, clear night,

Through a cloudless sky, as the moon shone bright,

One thousand bombers took off for Cologne.

Now, Albert Speer claimed (he was not alone)

That they never expected such a raid.

The damage was horrific, I’m afraid.

Over five hundred died. Churches were razed,

Some (you’ll be suitably shocked and amazed)

From medieval times or older still.

Half of Cologne’s houses (a bitter pill)

And public buildings were lost. The homeless,

In their thousands, roamed the streets in distress.

Tramlines, sewers, electricity, gas,

All were disabled at a stroke, alas.

The Cathedral was saved, God knows how

(Perhaps He does?). You can visit it now,

Standing proud in the new, restored city,

A fine example of antiquity,

Testament to the imbecility

Of war. Nonetheless, what truly mattered

Was this: public morale was not shattered.

German industry, too, was on a roll.

Despite the apparently awful toll

Exacted by the bombers at Cologne,

The British ‘success’ was overblown.

The Ruhr, Germany’s industrial heart,

Remained resilient. Harris apart,

Many doubted the bombing strategy.

Sir Arthur, though, ploughed on quite happily.

Churchill and Roosevelt (in ’43,

At Casablanca, in January)

Had little doubt. They were quick to agree,

In their preparations for D-Day,

That the allies should do more in the way

Of combining their efforts. Bombs away!

The US were ready to strike by day –

Their bombers were better equipped, okay? –

But with meagre success, I’m bound to say.

This caused, of course, not a little dismay.

Back to top / Buy the book

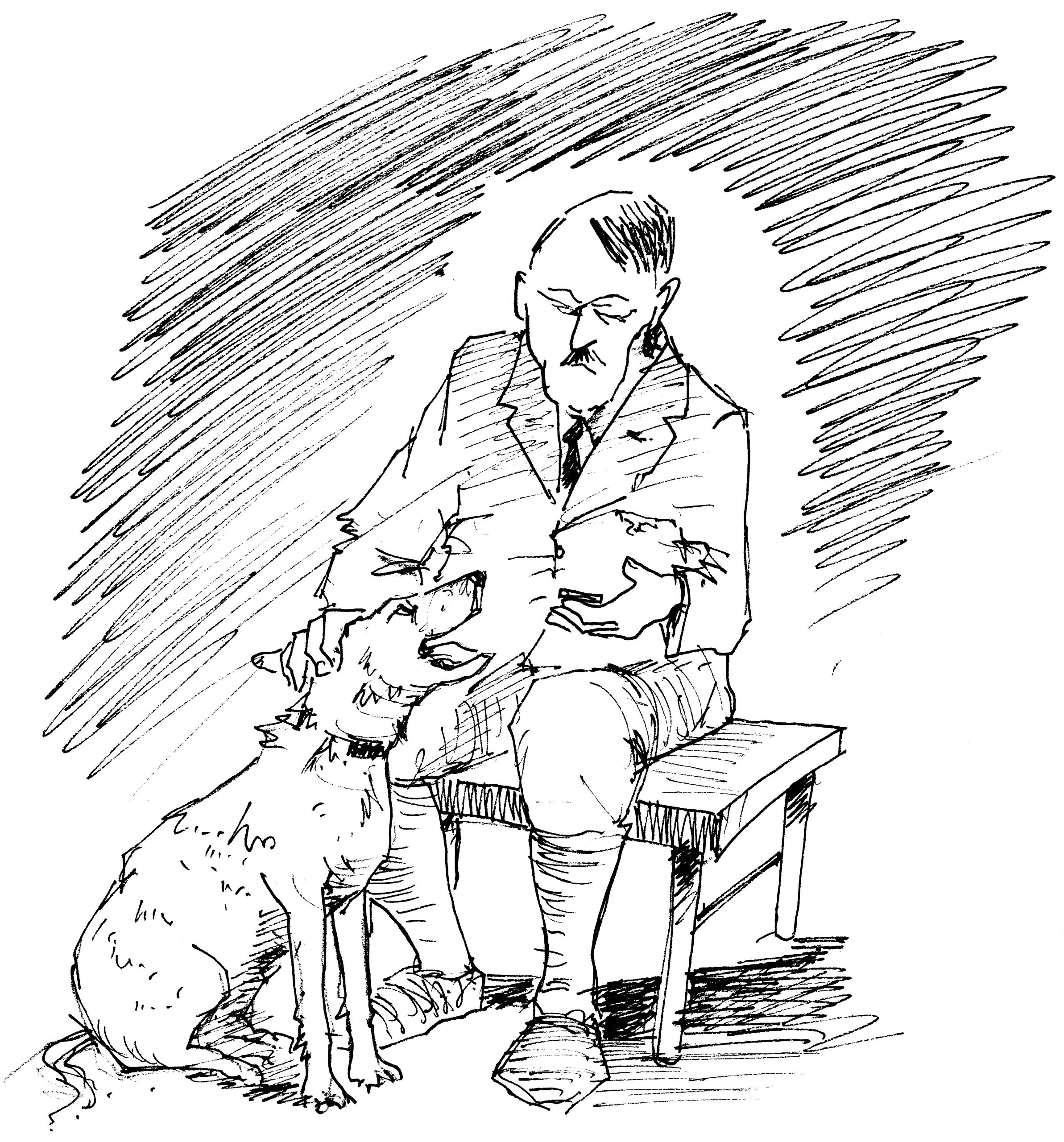

HITLER PREPARES FOR THE END

In case he should settle on suicide,

Hitler had ordered Himmler to provide

The wherewithal: capsules of cyanide.

Doubting now his former trustworthy aide,

The Führer paused. He was sorely afraid

That Himmler may have played a dirty trick –

Hard to believe, but far from fantastic –

And provided poison (hard to forgive)

That only knocked him out. He might still live,

To be taken to Moscow in a cage,

Perhaps… Yes, he was in a right old rage.

Animal lovers should now turn the page.

He took leave of his beloved Blondi,

His dog, second only (yes, honestly)

In his affections to Eva Braun.

Hitler fed her a capsule. Lying down,

The poor dog instantaneously died,

Painlessly, we hope. This was cyanide.

VE DAY

The PM was exhausted. On a roll,

To be sure, the war had taken its toll.

On VE Day he took lunch with the King,

With much mutual congratulating,

As indeed was only appropriate.

At 3 that afternoon Churchill saw fit

To broadcast to a grateful nation.

A great service of celebration

Was held at the Church of St. Margaret,

Westminster. Then the whole War Cabinet

And all the Chiefs of Staff, to their credit,

Trooped off to the Palace. The King and Queen,

In a special tribute rarely seen,

Led Churchill out onto the balcony

To greet the people (an amazing sea

Of faces, of smiles…) to a roar of cheers,

The like of which had not been heard for years.

Eight appearances he was asked to make,

Enough for an old man for goodness’ sake.

The two young Princesses, make no mistake,

Took part in the fun. Pretty and single,

The King allowed his daughters to mingle

(Chaperoned, of course) with the crowds that night,

Londoners at large. Sharing their delight,

Sisters Elizabeth and Margaret Rose

Had the time of their lives (one can only suppose).