Volume Eight – 1714 – 1760

The Early Hanoverians

GEORGE THE FIRST (1714 – 1727)

THE KING’S MISTRESSES

GEORGE THE SECOND (1727 – 1760)

GEORGE FREDERCK HANDEL

ALEXANDER POPE

BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE’S ESCAPE AND DEATH

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

SAMUEL JOHNSON

JAMES WOLFE

DEATH OF GEORGE THE SECOND

GEORGE THE FIRST (1714 – 1727)

When poor Queen Anne finally breathed her last,

Few were surprised. She had been sinking fast.

King George it was who now moved centre stage.

The German’s character was hard to gauge.

Some claimed he had a pretty, ready wit;

Others saw precious little sign of it.

At fifty-four a middle-aged figure,

Nonetheless the new King displayed vigour

And rude good health. His massive appetite

Was already a legend. Far from bright,

He inherited from his poor mother

Her passion for long walks, nothing other.

Languages? Pah! He spoke broken French

And barely any English. A great wrench

It was for him to leave his native state.

There he could speak German at any rate.

The arts (“boets and bainters”) he abhorred,

Though opera and music struck a chord.

Hunting, gaming and women, so we are told,

Were his passions. His subjects left him cold.

Shy and withdrawn, he was low on the skills

Expected of a King. Worst of these ills

Was his woeful lack of personal charm.

Though hardly a pressing cause for alarm,

One habit of his that provoked sniggers

Was his cutting out of paper figures.

Hours he’d spend on this bizarre pastime,

A quaint, if harmless, little pantomime.

Back to top / Buy the book

THE KING’S MISTRESSES

Hanoverian George (as we’ll call him)

Enjoyed a huge appetite for women.

His coming to England was attended

By two mistresses, no less: the splendid

Ehrengard Melusina von Schulenberg –

Was ever a title quite so absurd? –

And Charlotte Sophia Kielmansegge.

The King, in short, was a lucky beggar:

Two mistresses! Or was he? Old Ehrengard –

Maîtresse en titre – was held in low regard,

At least by the British. Bony and thin,

Scrawny and lanky and sharp as a pin,

This German phenomenon was greedy,

Voracious, power-mad and needy.

Moreover, she was superstitious,

Dim-witted and deeply religious.

Sixty if she was a day, the old trout

Was a snake-in-the-grass, without a doubt.

Mixed metaphors, sorry… Never mind that.

Where Ehrengard was thin, Charlotte was fat.

Horace Walpole met her as young boy

And offered this pen-portrait (far from coy).

The poor child professed himself terrified

By the apparition. Full as wide

As she was long, she boasted two “fierce” eyes,

“Black and rolling”, of quite enormous size,

Set beneath “two lofty arched eyebrows”. Vast

Were her cheeks (little Horace was aghast) –

“Two acres” they measured, spread with crimson.

Coquettish nonetheless (some said winsome),

She won George’s heart. Her “ocean of neck…

“Overflowed… her lower parts” (flippin’ heck!),

No inch of her body “restrained by stays”.

Good for her. Kielmansegge deserves praise.

Better than today, when the world expects

Women to walk around like stick insects.

Even Charlotte’s worst enemies confessed

To her brightness of spirit. To suggest

(God forbid) that her case smacked of incest

Would be a sin, a terrible libel.

Yet to swear otherwise, on the Bible,

Were impossible. For Charlotte’s mother

Had been George’s dad’s mistress. Oh, brother –

One awful scandal after another.

Whatever the rumours, George didn’t care.

Charlotte’s mum, as far as he was aware,

Was notoriously promiscuous.

It was manifestly ridiculous

To assume that his beloved Charlotte

Was his half-sister. A thoroughly bad lot

Was George. In my book what takes the biscuit

Is the mere fact he was prepared to risk it.

The obese Kielmansegge, however,

And the skinny Schulenberg, whatever

The parentage of the former, were both

Hugely unpopular and nothing loth

To exploit their high favour with the King

To feather their nests. This was sickening.

George’s subjects harboured a strong loathing

For the grisly pair. I’d say, on the whole,

Their nicknames (though cruel) were fitting and droll,

If predictable: ‘Elephant’ and ‘Maypole’.

Back to top / Buy the book

GEORGE THE SECOND (1727 – 1760)

Walpole had the job of telling the King

(The new one) tidings which, if anything,

Would afford him joy: his father’s demise.

Young George was having one of his ‘long lies’

(A euphemism this) with Caroline,

His beauteous wife. Well, the royal line

Must be peopled! Now, this was flaming June

And Walpole pitched up in the afternoon

At Richmond Palace. It may sound absurd,

But George was adamant: “Do Not Disturb!”

His valet de chambre was resistant

To Walpole’s request. Bob was insistent:

The King must be ‘woken’, and woken now –

No dithering. George was livid, and how!

He ambled down, his breeches half-undone,

A right royal shambles (pardon the pun),

To be met by Walpole, down on his knees

(All twenty stone), and informed, if you please,

That now he was King. “That is a big lie,”

He’s alleged to have said. No idea why.

Some thirty-three years later, quite alone,

King George the Second would die on the throne.

Please forgive this lapse into levity –

For ‘throne’ read ‘loo’. Life, in its brevity,

Deals a deadly hand. It’s a funny thing,

But George, for his sins, was told he was King

With his buttons undone (in open court)

And died on the lav (a sobering thought).

Back to top / Buy the book

GEORGE FREDERCK HANDEL

George Frederick Handel, the best of men,

Was employed by George (in 1710)

As his Kapellmeister in Hanover.

Handel wasn’t exactly bowled over

By life in George’s Herrenhausen Court –

All very boring, just boozing and sport.

He was twenty-five years old, after all.

Prospects of further advancement were small.

Handel, however, had achieved success

With opera – in Italy, no less.

A smash hit he enjoyed with Rodrigo,

Then tried his hand at oratorio.

This followed a farcical papal ban

On opera. From Florence to Milan

The word spread. La Resurrezione

Was a triumph in Rome. Il Sassone

(The Saxon) was George Frederick’s nickname.

He acquired, if not fortune, local fame.

But his post in Hanover paid the rent.

It was welcome, at least, to this extent.

Later in 1710 he sought leave

To pay London a visit. Up his sleeve

Was another opera, Rinaldo –

A sell-out success. Il Pastor Fido

Fared rather less well, as did Teseo,

Both performed on a subsequent visit

(In 1712). Life’s not fair, is it?

For both these works are frankly exquisite.

Handel’s popularity, nonetheless,

Grew and grew. A measure of his success

Was a new commission from Queen Anne

For her birthday music. A massive fan,

She granted him two hundred pounds a year –

A pension. The Elector, I fear,

(George of Hanover, as his boss still was),

Was far from content, if only because

He (George) wanted Handel all to himself.

Anne, never in the most robust of health,

Died, as you know, in 1714.

As Elector George succeeded the Queen,

Handel he ‘inherited’ (as it were).

The great composer had no cause to stir

From England again. A nice irony,

Given it’s where he was happy to be.

A most lucky accident. The new King

Was thrilled and proved most accommodating.

Handel’s pension he doubled. The rest

Is music history. Among the best,

George Frederick’s finest: The Messiah…

The Water Music… He was on fire!

Handel died in his seventy-fifth year,

Shortly before George the Second, I fear.

Here is what Ludwig van Beethoven said

(This is a quote): “I would cover my head

“And kneel before his tomb.” Take it as read,

Ludwig knew what he was talking about.

Handel had genius, beyond all doubt:

“He was the greatest composer” (some praise)

“That ever lived.” So he ended his days.

Back to top / Buy the book

ALEXANDER POPE

The undisputed poet of the age

Was Alexander Pope. How he’d enrage

His critics! In his famous Dunciad

He demonstrated the fun to be had

In destroying his foes – or the malice,

Rather. Satire is a poisoned chalice

In the hands of a twisted misanthrope.

This was the character, sadly, of Pope.

One example. Lord Hervey unwisely

Picked a quarrel. Pope, unsurprisingly,

Bit back with bile. “This painted child of dirt”

His Lordship became. How this must have hurt.

“Master” or “miss”? He acted either part,

With “trifling head” and a “corrupt heart”.

This (can you credit?) was only the start.

I won’t go on. The Dunciad this is.

I strongly advise you, give it a miss.

What brought Pope fame were his facility

Of phrase, his technical agility,

And his astonishing ability

To articulate the most commonplace

Of ideas with true poetic grace.

Form was all. As sharp and neat as a pin

Were his wit, his classical discipline

And his learning. Hang the cynicism!

Pope’s wondrous Essay on Criticism

Shows him at his best. Aged just twenty-three,

He distilled all critical theory,

All critical thought since Aristotle,

Into iambics! That takes some bottle.

Pope was on top form too (at full throttle,

Dare I say it) with The Rape of the Lock.

This mock-heroic satire was a shock,

So entertaining a work from this deep,

Earnest young man. You can laugh fit to weep,

Still, at the wonderfully trivial,

Witty diversion, convivial

Yet artful. A lock of Miss Fermor’s hair

Is snipped off by Lord Petre. Cue: despair!

The ‘epic’ works on many a layer:

A stylish romp; a social satire;

An heroic parody. Admire,

I beseech you, its brilliant allure,

Its perfect polish. You’ll love it, for sure.

I can’t confess to being a great fan,

But some profess that his Essay on Man

Is Pope’s finest. “Presume not God to scan,”

He writes. “Know then thyself… ” An odd, cold fish

Was Alexander, dry and stand-offish.

Of stunted growth he was since birth, poor chap,

Lonely, obsessive and ready to snap.

Let George the Second have the final word.

The King, we know, thought poetry absurd.

Advising Lord Hervey to avoid verse –

Poets were fanciful, vain and perverse –

Rhyming, he said, was a slippery slope.

Best “leave such work to little Mr. Pope”.

Back to top / Buy the book

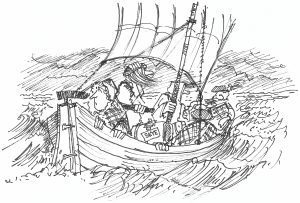

BONNIE PRINCE CHARLIE’S ESCAPE AND DEATH

Flora Macdonald was just twenty-four

When she met the Prince. Her jaw hit the floor.

She knew, of course, she was breaking the law

When a family friend, Captain O’Neil,

Casually asked her how she would feel

About helping Charlie over to Skye.

A brave young lassie, she didn’t ask why.

She gave her word and was glad to comply.

One fly in the ointment, hard to deny,

Was the head of the ‘hunt-the-Prince’ posse,

Sir Alex Macdonald (blunt and bossy) –

Step-father, no less, to our wee Flossie.

Flora cleverly exploited this fact,

Obtaining from Alexander (with tact,

And a fair dose of subterfuge) a ‘pass’

To cross to Skye. If this sounds like a farce,

It was. For on board was one ‘Betty Burke’

(An ‘Irish spinster and maid-of-all-work’),

A manservant, Flora and six boatmen.

Our Betty (you guessed, ten out of ten)

Was the Prince in person, got up in drag,

And so he escaped, the great scallywag,

“Over the sea to Skye”! I’m sad to say,

One of the sailors gave the game away,

But too late to worry Charlie. He fled,

And was soon back in France, safe in his bed.

Flora was arrested on her return.

Cool, composed and showing little concern,

She denied that she had lessons to learn.

She had acted, not out of recklessness,

But as anyone would for one in distress.

She didn’t languish in prison for long.

Few folk believed she’d done anything wrong.

George, in his wisdom, the following year,

Granted a general pardon (hear, hear!)

To all those rebels who pledged loyalty.

Flora, at heart, respected royalty.

She bore five boys. They served the King to a man,

Patriotic sons of the Macdonald clan.

As for Charlie, his was a barren life.

His Highland adventures, with drum and fife,

Yielded him little but loss and despair.

He wandered any- and everywhere,

The length and breadth of Europe. For six years

Even the old ‘King’, his father, one hears,

Lost trace of his whereabouts. Charlie’s tears

Watered the precious soil of Lorraine,

Austria, Italy, Russia, Spain,

Sweden… He popped up in Scotland again,

Even London. He never gave up hope.

But when his father died, neither the Pope

Nor any European head of state

Hailed ‘Charles the Third’. It had been a long wait.

James outlived two King Georges (saints alive!).

When he breathed his last, his son was forty-five.

Charles struggled on for twenty-two more years –

A sad, pathetic figure, it appears.

He took to the bottle. He left no heir.

The last of the Stuarts. A sorry affair.

Back to top / Buy the book

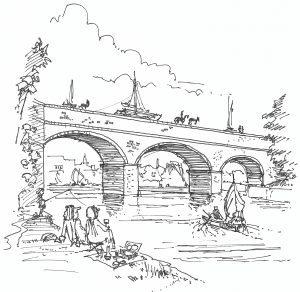

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Let’s talk of mills and mines. There was a whiff

Of revolution in the air, as if

Britain was poised on the very threshold

Of a new age. No one could have foretold

The scale of change, the suddenness, the speed,

The voracious energy and greed

Of the ‘Industrial Revolution’,

So-called. Ruin, disease, destitution,

Misery, ill health – these marched hand in hand

With a huge surge of wealth throughout the land:

The ‘white heat of progress’, you understand.

A steady growth in the population

After 1740 (the nation

Grew by an astonishing ten per cent,

Half a million, in twenty years) meant

Not only cannon fodder for the wars,

But cheap and plentiful labour. The laws

Were lax. There was no regulation,

No restraint on the exploitation

Of children or the vulnerable poor.

A complete free for all. This I deplore.

The century had worse horrors in store

Than were apparent at this early stage.

Indeed, as more folk lived to middle age

Through medical advances, and new wealth

(From trade) meant better economic health,

Men were optimistic. Agriculture

Was booming, with the dash for enclosure.

The state of the roads, a former disgrace,

Continued, we’re told, to improve apace,

With a large increase in turnpike trusts. Coke

Was first used by an enterprising bloke

Named Abraham Darby in the process

Of smelting, which saw a sea-change, no less,

In the production of iron. John Kay

Is a largely unsung hero, but hey,

His ‘flying shuttle’ speeded up the way

Weavers made cloth, a breakthrough in its day.

Halting advances, it has to be said,

Compared to the marvels that lay ahead,

But the seeds were being sown. Momentum

Was gathering. A perfect exemplum

Was James Brindley’s remarkable design

For a canal to travel in a line

From Worsley (the Duke of Bridgewater’s seat)

To Manchester, to ferry coal. Some feat.

Brindley, an illiterate engineer,

Was bright and forthright, a stranger to fear.

His waterway crossed the River Irwell

By bridge, at a height of forty feet. Well!

There were no locks. The water was contained

By high embankments. Imagine: untrained

And unlettered. How can this be explained?

Pure native genius, that’s what I say.

It could sadly never happen today.

The price of transporting Bridgewater’s coal

Was halved at a stroke – a blow, on the whole,

To the sceptics. Canals were here to stay.

Brindley was on a roll. Anchors aweigh!

Back to top / Buy the book

SAMUEL JOHNSON

The literary figure of the age

Was Samuel Johnson. Essayist, sage,

Critic and eccentric, his anecdotes,

Assertions, aphorisms and choice quotes

Have been immortalised by James Boswell

In his famous Life. Johnson cast his spell

Over literary London. “No love”

Had he “of clean linen”. Heavens above!

Yet I’ve read that a more clubbable man

Was not to be found. His career began

As a humble, lowly paid schoolmaster,

Unsuccessful (indeed, a disaster) –

Save for the odd fact that David Garrick

Was his early pupil. They seemed to click,

And both set out for London together

To try their luck, whatever the weather.

Garrick, the foremost actor of his time,

Drew the crowds at Drury Lane. In his prime

He gave his Lear to explosive acclaim.

The Doctor took longer to make his name.

Sam struggled. Oxford University

He left, with regret, without a degree,

Despite being hailed as a prodigy

In Latin and Greek. He was twenty-eight

When he left for London – that’s pretty late.

He laboured as a jobbing journalist –

Deadlines and drudgery, you get the gist –

Reporting tedious late-night debates

In the House of Commons. One hesitates

To dwell too long on his early career,

The Rambler the only highlight, I fear.

This was the Doctor’s own publication.

Its far from unhealthy circulation,

Twice weekly, topped five hundred. Politics,

Society, literature, ethics,

Religion – these were Johnson’s topics,

Explored as essays, often as stories,

And sometimes even as allegories.

A rare achievement, distinctive in tone,

Earnest in purpose, The Rambler’s alone.

Johnson’s Dictionary made his name,

Affording him lifelong honour and fame.

In two massive volumes, this giant work

Took our towering literary Turk

Nine years of toil to complete. It’s very long –

Some 42,000 entries. Right or wrong,

Sam could lapse from his serious mission

To slip in the odd, quirky definition

For light relief. “Oats” (he gives no sources):

“Which in England is given to horses,

“In Scotland to men.” And (he the best judge)

“Lexicographer: a harmless drudge”.

The Dictionary is tight. There’s no fudge,

No waffle. You’re left with that vital sense

Of Johnson’s lifetime of experience

In reading. He’d rarely finish a book

Or ever need to take a second look.

The Doctor nonetheless absorbed it all:

A photographic mind; total recall.

For Johnson was forty, never forget,

When he took up his challenge. I should bet

(Were I asked) that he could conjure at will

A quote, an instance, with consummate skill,

All from memory. It sends a small thrill

Down my spine. The ponderous French, one hears,

With forty ‘experts’, spent one hundred years

Compiling their lexicon. That’s quite sad.

Six amanuenses Samuel had.

Yes, that’s right, you heard me: six. He was paid

(For once) for his labours. I’m told he made

Fifteen hundred and seventy-five pounds.

That’s quite a sum, affording ample grounds,

I suspect, for this assertion (I quote):

“No man but a blockhead ever wrote

“Except for money.” Oh, would that were true!

But writing for pleasure is nothing new.

It’s not such a terrible thing to do.

Our Sam was a staunch Tory. He believed

That raising a worker’s wages relieved

Him not from poverty, but from hard graft.

In his judgement it was plain daft

To seek to make a labourer better

By paying him more, when the true debtor

Was society. It made men idle

To raise wages. It was suicidal.

His general outlook, I think you’ll find,

Was more reactionary still. “Mankind

“Are happier,” so Johnson opined,

“In a state of inequality

“And subordination.” Not pretty.

Still, to his credit, he loved his wife

And never tired of London life.

Back to top / Buy the book

JAMES WOLFE

Wolfe was a commander hand-picked by Pitt.

The King would regularly throw a fit

As Will proposed a startling array

Of fresh new blood. But Pitt, as was his way,

Would press the deaf old King and win the day.

In Wolfe’s case, happily, it’s true to say

That George was pretty easily convinced.

Newcastle, I’ve read, positively winced

When Wolfe was tipped for senior command.

The King proffered this witty reprimand:

“Mad, is he? Then I hope that he will bite

“Some of my other generals!” Quite right.

George, on form, was an absolute delight.

Young James Wolfe had a talent fit to burst.

Valiant, sensitive and with a thirst

For discipline, he served under Amhurst

At Louisburg (Pitt’s appointment, of course).

A stickler for detail, a workhorse,

And yet physically frail, Wolfe, perforce,

Led by example. Under heavy fire,

He was first off the boats. This I admire.

So it was, on the 12th of September,

’59, truly a night to remember,

Wolfe prepared his men in an enterprise

Of rare strategic genius – the prize:

Quebec. Up the St. Lawrence, in small boats,

With muffled oars, he led his brave redcoats

(Some 5,000) under cover of dark.

No owl was heard to hoot, no dog to bark,

No gull to cry. The silence of the night

Bore but one sound. Wolfe was moved to recite

Gray’s Elegy. Madness? One of the signs?

Hardly. He’d rather have written these lines,

He told his fellows, than take Quebec. Well,

You can see why men fell under his spell.

Part of the British fleet, some miles away,

Began a bogus bombardment, to essay

A diversion, as Wolfe led the way

Up the Heights of Abraham – yes, a cliff.

There was no going back. Retreat? As if.

The French were taken wholly by surprise.

They woke on the 13th, rubbing their eyes,

To behold the Brits, complete with supplies

(And guns), apparently dropped from the skies.

The French were something of a rag-bag force:

A hard core of regular troops, of course,

But weakened by Indians (in war paint)

And local militia – somewhat quaint,

If the truth be told. Wolfe had little doubt,

Should he hold his nerve, he could put to rout

This ill-prepared detachment. He was right.

The French put up some semblance of a fight,

But were shot to pieces. And so, good night

To the French in Canada. Quebec fell.

James Wolfe’s fine triumph sounded their death knell.

Our hero was thrice wounded that day.

He died with honour and was heard to say,

“Now, God be praised,” (he knew the day was won)

“I will die in peace”. Wolfe’s place in the sun

Was ever assured. His duty was done.

Back to top / Buy the book

DEATH OF GEORGE THE SECOND

If this reads like an obituary,

So it is. Late in 1760,

On October the 25th, the King

Rose early (six o’clock in the morning),

Drank his daily cup of hot chocolate,

Then retired (as was also his habit)

To his privy. There he suffered a fit –

From a ruptured ventricle of the heart.

His valet de chambre gave quite a start

Upon hearing a noise “louder,” we’re told,

“Than the royal wind”. The King was out cold.

George the Second had fallen off the loo.

Nothing that the royal surgeons could do

Availed him one jot. They bled him, of course –

A treatment more fit to kill off a horse.

The King’s hour had come. Old, deaf and blind,

His passing was a mercy. Death was kind.

George has been neglected, I think you’ll find,

By posterity. “The late good old King,”

Was Pitt’s epitaph. More nauseating

Was Newcastle’s estimate (why pretend

That George had treated him well?): “the best friend

“That ever subject had.” Hypocrisy!

Cant! Compare Pitt: “…in an eminent degree

“He possessed justice, truth and sincerity.”

Now that sounds more honest and heartfelt to me.

George died sixteen days before his birthday,

His seventy-seventh. As is the way,

All eyes were turned to the new King. My view,

For what it’s worth, is that George the Third knew

Nothing! He was immature, twenty-two,

Cocksure and untutored. What did he do?

Well, for starters, he replaced Pitt with Bute,

The bumbling Earl, as thick as a boot,

Yet ‘in’ with the King. George may have been cute

And blessed with a certain swagger and flair,

But Britain, alas, was soon in despair.

The country was strong, its economy

Robust, a land of opportunity

And plenty. Folk gave credit to their King,

His fine example much to their liking.

For old George was courageous, loyal,

Beloved of his subjects. The perfect royal?

Well, hardly. To make such a claim were absurd,

But hold on to your hats. Bring on George the Third.

Back to top / Buy the book